Crimes of the Art?

holden steinberg

Eight years after Larry Rivers’s death, both his pioneering art and his hypersexual private life are getting fresh attention. In the 70s, he filmed his adolescent daughters topless for a documentary, Growing, that the younger one, Emma Rivers Tamburlini, says is nothing less than child pornography. With battle lines drawn between Emma and those who guard Rivers’s legacy, the author asks whether the artist was shattering taboos or destroying innocence.

On a late-September evening, an art-world crowd swarms through the high, dark spaces of Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art for the opening of “Abstract Expressionist New York,” a show drawn entirely, and remarkably, from MoMA’s own basement—for this is the art that the museum, under the aegis of late, great director Alfred Barr, began snatching up in those postwar days when a Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning could be had for a pittance. And MoMA had a lot more than that to spend.

“PERHAPS, INSTEAD OF SEEING ME AS A ROSE AMONG THORNS,” SAYS EMMA, “MY FATHER SAW ME AS ANOTHER THORN.”

But what’s this? Here amid the masters of anti-figurative art is Washington Crossing the Delaware, a more or less representational painting by Larry Rivers. And there, in front of it, is most of Rivers’s three-family clan, gazing at his 1953, career-making work with a mix of pride and love—and, for his daughter Gwynne, 46, hurt and anger too. “It’s the first time I’ve seen it,” she says softly, for the sizable canvas sat in storage for 25 years until MoMA curator Ann Temkin came upon it this year and muttered “Wow.”

The painting isn’t what’s stirred those darker feelings in Gwynne. It’s another work by her father that’s just come to light, one that’s haunted her since she was a pre-adolescent.

Eight years after his death, Rivers’s critical reputation does seem to be on the upswing. In addition to its presence in the MoMA show, his work is prominently featured through February 13 in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition of sexual difference and desire, “Hide/Seek,” in Washington, D.C. Soon after, a one-man show opens at New York’s Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Most important, Rivers’s archives have just been sold for an undisclosed sum to New York University, giving scholars reams of new material to burnish his legacy. But the one-time bad boy of the New York art scene, known as much for his sexual exploits and provocative nature as for his paintings, is also under attack. His accuser is his other daughter, Emma Rivers Tamburlini, 44, a no-show at MoMA this evening, for she has no wish, she says, to see any of her four siblings or publicly celebrate the father she regards as her longtime tormentor. Emma declares her father guilty of nothing less than child pornography, over a period of six years, with herself and Gwynne as his unwilling subjects.

It was the archive sale, announced last summer, that led Emma to take her charge public. Amid the archive’s thousands of letters, pictures, and paraphernalia is a collection of videos made by Rivers in the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s. Like Andy Warhol, Rivers saw video as a new art form. Unlike Warhol, he used it mainly to explore sexual taboos. In 1976 he had Gwynne, then 11, participate in a film called Growing by baring her breasts before the camera and discussing how she felt about them. He also filmed Gwynne nude in his shower and had her slip topless between the black satin sheets of his bed. A year and a half later, Emma was conscripted, too.

Twice a year for four more years, the daughters submitted to filming sessions, sometimes just with their breasts exposed, sometimes naked, as their father asked them questions about their bodies and budding sexuality. In the early 1980s, Growing was edited, and screen credits were added; Rivers planned to play it in a continuous loop at a show of his paintings. Dissuaded by Clarice, the girls’ mother, from doing that, he put the film and its outtakes on a shelf, to be forgotten by almost everyone—except Emma and Gwynne.

The same day that David Joel, director of the Larry Rivers Foundation, e-mailed the family to announce the archive sale, he sent a separate e-mail to Emma, assuring her he had negotiated tight restrictions on Growing with N.Y.U. No one would be allowed to view the film in Emma’s lifetime. “What a comforting thought,” as Emma put it later in one of a series of e-mails toVANITY FAIR. Emma had made Joel aware of her feelings on other occasions: nothing less than having the footage handed over to her—to be destroyed—would do.

When he wouldn’t, Emma took her story to The New York Times. She told Kate Taylor, the Timesreporter, that the filming had contributed to the anorexia she began suffering at 16. “It wrecked a lot of my life, actually,” she recalled.

Startled, N.Y.U.’s dean of libraries declared the university wanted no part of Growing. It could stay with the foundation, which could then reach its own understanding with Emma. There the video resides, for Joel, backed by his fellow board members—who include Rivers’s sister Joan Gordon, 80, and one of his three sons, Steven, 65—refuses to hand over Growing to Emma. He says the film must be preserved, both as source material for a large Rivers painting of 1981, which incorporates still images from the movie, and as art in itself. (Rivers’s other sons, Joseph, 70, and Sam, 25, agree the film should be preserved.)

“You know a major artist made this film, right?” says David Levy, a longtime friend of Rivers’s. A former head of Parsons school of design, a former director of Washington, D.C.’s Corcoran Gallery, and a nonfamily member of the Rivers Foundation board, he adds, “You also know that his extremely neurotic daughter, who has had a lifelong problem with her father, has raised a stink about this. So think twice before you destroy any work made by a well-known artist—more than twice.” (“What does David Levy consider a non-neurotic position for me to take?” Emma asks in response. “I guess he would have liked me to just shut up.”)

At a sidewalk café on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Gwynne Rivers tries to stake out a middle ground. Graceful, with long chestnut hair and searching eyes, she was, of the two sisters growing up, the extrovert, singing bluesy torch songs with her father’s jazz bands. Now she’s an art adviser and mother of three, married to an investment banker. Her sister’s campaign caught her by surprise. “We never had a conversation aboutGrowing our entire lives,” Gwynne says. “I did talk about it in therapy, but not to friends or even my husband.” She was stunned by the story in the Times: Emma did that on her own.

On reflection, Gwynne has had to admit that Growing did her real damage. “I just made it go away,” she says. “Unsuccessfully.” She struggled with bulimia as a teenager and drank to excess into her early 20s, until she got sober. She had difficulty connecting emotionally with men. For years she’s been involved with a women’s therapy group that deals with sexual-abuse issues. “I’m not saying it was all the film Growing, but … that careless attitude on my father’s part.”

Gwynne says she gave her father a break while he was alive. “I don’t want to cut him a break anymore. I think he knew better. Maybe I could have understood if he started on day one with this idea in mind, sees his daughters are uncomfortable, and says, ‘O.K., this isn’t working, this is bad.’ But he didn’t. And he knew he was making us uncomfortable, because he says this in the voice-over: ‘Much to the confusion of my children and family, I continued.’ Maybe every father has some feelings about his daughters turning into young women, and they know it’s verboten, so they don’t go near it. My father knew it was verboten, so he found a way to luxuriate in his fantasies without, he thought, putting both feet over the line.”

Gwynne has made progress in coming to terms with her father, who, as she puts it, loved her “in his own wacky way.” She’s more intrigued by the film than incensed—in part because she’s never seen it in its final form.

With Emma it’s a different story. “At some point, I stole a copy of the final version of Growing,” she acknowledges. “I wish I had taken them all, but I was still a ‘good’ girl not willing to make too much trouble.” Now she’s passed her copy on, she says, to an assistant Manhattan district attorney, Emily Logue. According to Emma, Logue has viewed it with alarm and is considering confiscating all copies as obscene material. (Logue would not comment on what the D.A.’s office considers an open investigation.) “David Joel has been spending too much time in his quiet little art attic in the Hamptons,” Emma writes in one of her e-mails, “to know the rest of the world has moved forward from the 70s and 80s, and now people actually want to protect children better.”

It Took the Village

The Rivers archive, soon to be moved to N.Y.U., fills an unobtrusive, wood-shingled house near Bridgehampton’s railroad station, on Long Island. David Joel, 47, is the tall, earnest, bespectacled but incongruously buff preserver and protector of the treasures within. He started working in Rivers’s studio as a graduate student in 1985 and never left. At one point he had a life-threatening illness and Rivers offered to pay him merely to sit in a chair. (Joel never took him up on the offer not to work.) Not surprisingly, Joel loved him, as did many others.

To judge by the cabinets and boxes within, Rivers kept everything—every letter written to him, every picture he took, and every film he made, the reels shelved in white boxes on a bathroom wall and hand-marked. Here, too, are 635 paintings that won’t be included in the archival transfer. Before packing it up for the National Portrait Gallery show, Joel unveils Frank O’Hara in Boots, a nearly eight-foot-high 1954 portrait, in deep, strong browns and muted flesh tones, of the influential New York City midcentury poet and art critic, proudly naked but for his boots. It’s vintage Rivers: beautiful, startling, and gleefully provocative, even for those with no idea that O’Hara was Rivers’s lover.

Rivers’s paint-smeared worktable is in the basement, the squeezed and twisted tubes of oils exactly as he last touched them, the Martinson coffee can still holding his brushes in a horsehair bouquet. So is Rivers’s saxophone, in its scuffed and ancient case: the start of his story as an artist.

From her Watermill, Long Island, house by the ocean dunes, one of Rivers’s oldest friends, the painter Jane Freilicher, 86, recalls that saxophone and the first day Rivers thought about painting. At 22, the Bronx-born Yitzroch Loiza Grossberg, whose parents, to his lifelong dismay, spoke English with a Yiddish accent, had joined a jazz band for a summer job in the seaside resort town of Old Orchard Beach, Maine, escaping not only his roots but his pregnant wife, Augusta, and the young son she’d brought from a previous relationship. Jane, 21 that summer, was the gorgeous wife of one of his bandmates, Jack Freilicher. “Larry asked me about my sketchpad,” remembers Freilicher, “and he started fooling around with the watercolors himself.” Freilicher went on to a long, distinguished career as a landscape painter. Only half joking, she adds, “He wouldn’t have been a painter without that meeting!”

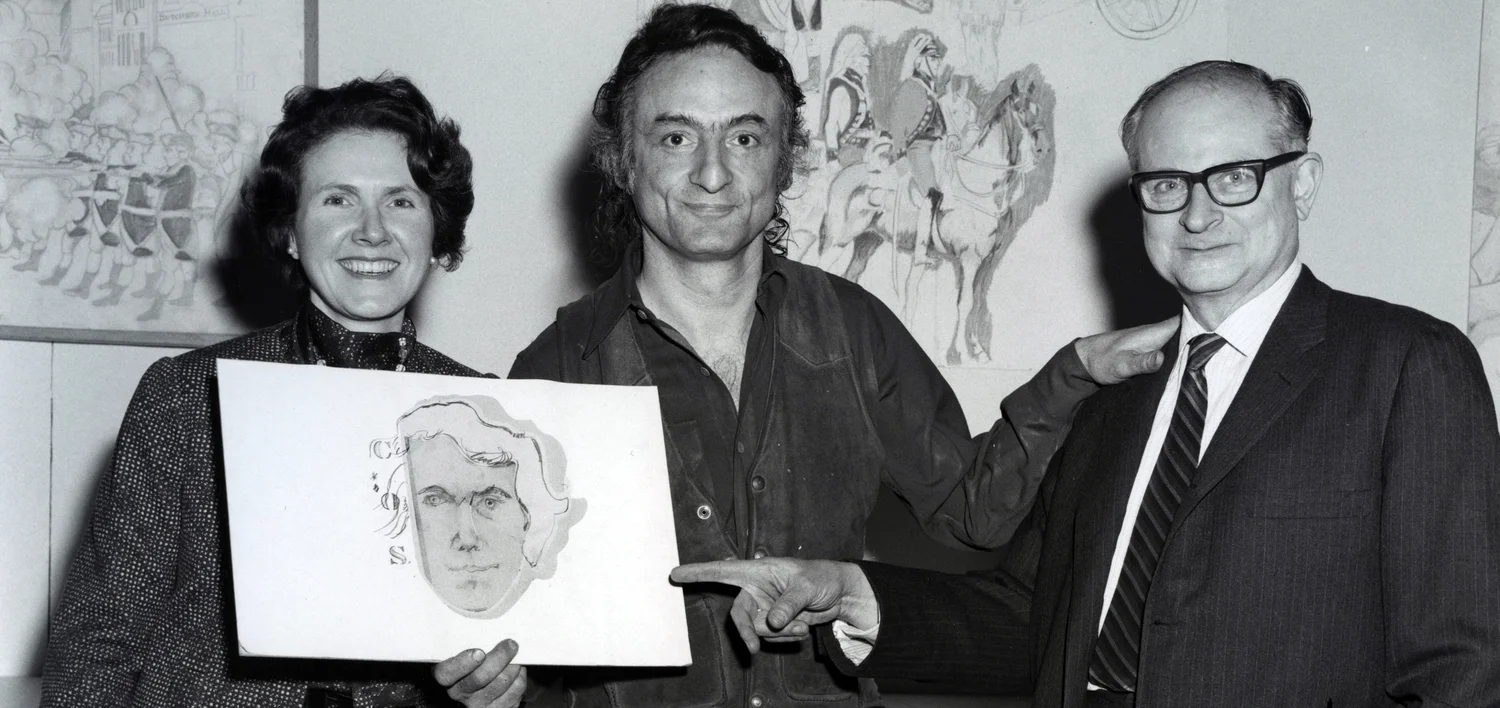

The year was 1945. Back in New York, Freilicher brought Rivers to the scruffy salons of the young New York School painters and poets. His fierce, Semitic features, especially the prominent nose, along with his personality, made him seem, as one of his later lovers, Phoebe Legere, would put it, part eagle and part devil. “He was dynamic, he was talkative, he was deliciously vulgar, he was fearless,” recalls photographer and writer John Gruen, who at 19 had married the landscape painter Jane Wilson and remains married to her still. “We hung out at the Cedar Tavern, together with the de Koonings and the Pollocks, who were already huge influences, even on Larry Rivers, who never followed their style.”

Abstract Expressionism was in, figurative painting out, all but forbidden, but Rivers, a rebel to his toes, began questioning that. “There was an artists’ club on Friday nights,” recalls Al Kresch, a fellow artist who helped form the seminal Jane Street Gallery. “Whoever talked—Motherwell or de Kooning, about Mondrian or Arp—Larry would get up and say, ‘Doesn’t Renoir count?’ Which was like a slap in the face.”

But it was not until 1953 that Rivers became a star—with Washington Crossing the Delaware. In his 1993 biography of Frank O’Hara, Brad Gooch described the painting’s subversive nature: “Its parodistic figure drawing … was a battle cry, thumbing its nose at Abstract Expressionism and pointing the way toward what would later become Pop Art.”

Rivers was breaking sexual boundaries, too. If both men and women wanted him, why not? The sex he engaged in with most of his male admirers he viewed as an adventure. With O’Hara, it was much more. The two were soulmates and, for a while at least, lovers, but O’Hara was more infatuated with Rivers than the other way around. “I’m not equaling your desire to see me with a desire to see you,” Rivers wrote in one of the dozens of tightly spaced letters the two exchanged over more than a decade—the correspondence that’s now a crown jewel of the archive.

“Larry’s gay side always struck me as the result of his desire to shock people,” the poet John Ashbery writes in an e-mail, “rather than the extension of a deep-seated urge.” Joan Gordon agrees. “He was a heterosexual who would do it to a pig to see what it was like!”

As an artist, Rivers was fascinated by the human body—male and female. In the nudes he used as his models, he broke more boundaries. Divorced, with custody of his two sons, Rivers induced his ex-mother-in-law, Berdie, to pose for him en déshabillé. A number of paintings from the mid-50s show Berdie, a meek soul, in all her sagging corpulence. Before long, Rivers was painting his sons nude, too, which neither boy minded at all until the day Joseph, at 14, heard that the latest nude portrait his father had done of him was hanging at Keene’s bookstore on Southampton’s Main Street.

“I was horrified,” recalls Joseph Rivers with amusement, “because all the kids at school came to see it before the police made him take it down. But in a way it was a case of ‘There’s no such thing as bad publicity.’ Because it made me a star for a week, and being a star ain’t easy to come by!”

At 70, Joseph, who has three children from three marriages, lives alone on the outskirts of Poughkeepsie, New York. He is proud of his father’s artworks (many of which hang on his walls), including the nude paintings of himself and his brother Steven. “There was no sexual overtone,” he says. “Larry didn’t think in a pornographic way. He would examine anything and take it apart and put it together again. That’s what he did with art, with the paintings of us nude. If Emma knows that this was his M.O., why does the film bother her? I have to stress that I’m not in her shoes. But it’s hurt me because … it’s taken the whole focus of what Larry’s career and achievements were, and pushed it aside. Instead, the focus has become her chest. I think it’s a very selfish thing to have done.”

Steven Rivers, five years Joseph’s junior, lives across the Hudson and works as a therapist in a small town. He has many warm, loving memories of his father, seemingly unaffected by the long hours spent modeling in the nude as a boy of 10 or 12. “Joe and I had a stage of his life that was special,” Steven says, “when he was wilder and crazier, but also had more time for us. As he got older, he had less patience in terms of trying to fit his children in. My sense is that Emma and Gwynne felt very deprived, and that deprivation manifested itself in different ways.” The result, says Steven, is that “Emma is trying to destroy whatever is left of our father.”

In early 1960, Rivers needed an au pair for Steven, so he sent for one from England. “I was there the night Larry picked up Clarice,” recalls the writer Barbara Goldsmith of the 21-year-old carpenter’s daughter who arrived that February night. “He was shocked at how attractive she was. And a great cook too!”

Rivers’s girlfriend at the time was the redheaded beauty Maxine Groffsky, a onetime lover of novelist Philip Roth’s (she was the model for Brenda Patimkin in Goodbye Columbus), an editor of the Paris Review, and later a literary agent. “Larry was amazing and outrageous,” Groffsky recalls. Though perhaps, as an artist whose jazz life had led him to dabble in heroin, not the best boyfriend material. (“I just thought he had the flu,” Groffsky recalls, “which I treated the way any nice Jewish girl would, with chicken soup.”) Out went Groffsky, in came Clarice Price, who was happy to become Rivers’s second wife and, in time, the mother of Gwynne and Emma.

Rivers by now was the life of the party—an art-world party that moved between Manhattan and Southampton. For a few more years it went on, with Rivers the artist riding the crest of Pop art and, in his personal life, happy with the sexy, young wife who gave birth to Gwynne in 1964. Then, one night—July 25, 1966—the music seemed to stop.

Frank O’Hara was killed, at 40, in a freak accident on Fire Island, when a vehicle ran over him on a beach in the dark. Though their romance had cooled years before, O’Hara had remained Rivers’s best friend, his muse, and, as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, an essential champion of his work. O’Hara had just been buried when Emma was born. “I always think of the time I was born as a sad time for my father,” Emma writes in one of her e-mails. “Frank O’Hara died two weeks before, and perhaps, instead of seeing me as a rose among thorns, my father saw me as another thorn. He wanted to name me Franco America. My mother intervened.”

Not long after, Clarice moved out, taking her young daughters to live in an expansive apartment on Central Park West. She and Rivers never divorced. Instead they managed such an amicable separation that they often attended parties together, much to the annoyance of the ever younger girlfriends Rivers had in tow. Clarice paid the girlfriends no mind, and Rivers was delighted when she, in turn, took up with a German prince, Rainer von Hessen, whose uncle was Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. “[Rainer] was entirely likable: generous, kind, loving, soft, gentle, very encouraging,” Gwynne recalls. Unfortunately, after seven years, Clarice brought the romance to an end, and the prince decamped. “His leaving was tough on us both,” says Gwynne, “but perhaps more so on Emma.”

Of the two sisters, Gwynne felt a greater kinship with their father. Emma felt somewhat removed. Going to her father’s loft, she says, “was like visiting a distant relative.” She was closer to her mother and to Rainer. With his departure, both girls sought more from Rivers.

“LARRY DIDN’T THINK IN A PORNOGRAPHIC WAY.... IF EMMA KNOWS [THIS], WHY DOES THE FILM BOTHER HER?”

Video Jockeys

By 1976, video cameras had made moviemaking far easier, and Rivers had a new collaborator, the mischievous, seductive Michel Auder, at loose ends after the breakup of his marriage to Warhol-movie star Viva.

Auder came to live at Rivers’s new loft, an astonishing block-long space on East 14th Street, and followed him with a camera wherever his sexual curiosity took him. “Larry would be miked, and I would be shooting with the camera,” Auder, now a video artist living in Brooklyn, explains. “He would do most of the interviewing. He would start asking very personal questions. It made the world interesting that way. Also, it was gross, but in a good way, and shocking in a good way, because people are more repressed than they know—they don’t like to voice these things.”

One film was on transsexual prostitutes. Another was about Chicago Seven leader Abbie Hoffman’s getting a vasectomy. When Steven became a sperm-bank donor to earn a little extra money, the video crew followed. Rivers even made a movie about his mother, Shirley, featuring a scene in which she gave him an enema. “Larry just had this view that everything was fair,” says David Levy. “He didn’t see the boundaries.”

Emma did.

“My father gave me and my sister private screenings (only with him) when I was ten through about twelve,” she writes. She remembers the one about Steven as a sperm-bank donor, in which, she recalls, he masturbated into a cup. (“It does not show me masturbating,” Steven says. “I’m in the bathroom, the door is closed, and my father is outside with the camera asking, ‘Is everything all right?’ It was actually a very funny movie.”) Another was “The New V,” an exploration of the new vagina of a woman who’d just had a sex-change operation. As Emma recalls it, “Michel Auder … stuck his fingers up into ‘the new V’ to report to my father, who was filming, if it felt genuine or not. Michel said it did.”

The sessions for Growing began with Rivers encouraging the girls in some innocent fun: setting up cushions on the floor for somersaults. “ ‘Why don’t you start by singing a song for me?’ ” Rivers asked Gwynne, as she recalls. “So I would practice a song, and I was proud of getting it captured on film.” Then would come the uncomfortable part. “To go from singing a song for your father and then to suddenly be told to take off your shirt … the dread in my stomach when I heard those words drowned out the lovely feelings of performing for my dad—it broke down to what he really wanted to see: my breasts.” One of the first times, she remembers, she sang the Beatles’ “Yesterday”—“which seemed apropos, because my childhood was a real childhood, and then suddenly it wasn’t. I remember being very sad singing, ‘Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away, now it looks as though they’re here to stay.’ And so they were: from that point on, I began to kind of disconnect myself. I wanted to be a strong, hard person so nothing could hurt me.”

In at least one session, according to The Southampton Press, a local paper, Clarice took off her top, too, and talked about her own breasts. To the reporter, Clarice explained that she didn’t want her daughters to go topless while she refused. But Gwynne thinks there was another reason her mother participated. “She was young, and here totally on her own as far as family was concerned, and my father had a way of making everything seem like it was part of his artistic vision. I think she bought into that very much as well.”

“TO GO FROM SINGING FOR YOUR FATHER,” RECALLS GWYNNE, “THEN TOLD TO TAKE OFF YOUR SHIRT ...THE DREAD.”

Emma takes a harsher view: her mother was a willing victim of a husband who was, deep down, a misogynist. “Did you ever see the painting my father made of my mother, ‘In Celebration of Shakespeare’s 400th Birthday: Titus Andronicus’?” Emma writes. “On a large canvas (maybe 5 x 7), he depicts my mother with her arms and legs hacked off, her tongue cut out, and blood gushing from her stumps. She’s nude with her legs spread. My mother had this proudly hanging up in her living room or dining room for thirty years. She didn’t take it personally. The perfect model.”

“I never minded how an artist wanted to represent me,” Clarice says. “I didn’t have an ego about that sort of thing.”

‘Whatever his defects were, he was always around the kids, and they around him,” recalls writer Barbara Probst Solomon, a family friend. In a 1993 documentary by filmmaker Lana Jokel, Emma said of her father, “He has a wonderful mind. I always loved hearing his opinions about politics and art.” In the same documentary, Gwynne said of him, “The way he advises me is with a tremendous amount of respect: ‘You have to find out who you are.’ ”

And yet family life, to two girls at formative ages, was complicated. Michel Auder had moved in with Clarice—a new father figure of sorts, though perhaps an awkward one, given that he’d helped make several of Rivers’s sexual films. Diana Molinari, a nanny for the girls, had moved into Larry’s loft as a sometime girlfriend. There at the loft, too, in various shifts, were Sheila Lanham, who’d met Rivers when she was 22, and Daria Deshuk, a 25-year-old art student. “It was always like that with Larry—undefined,” Lanham recalls. As a wide-eyed girl with Appalachian roots, new to New York City, she had no objections to Molinari’s sleeping halfway down the block-long loft, or even to Deshuk. Both also learned to accept Clarice—in Lanham’s case, through gritted teeth—and embraced Emma and Gwynne. In 1985, Deshuk had Sam, Rivers’s third son and last child.

By then, the pack included Phoebe Legere, a young jazz singer and artist. “I think Emma and Gwynne, because he was the father, they cannot see him the way I saw him,” says Legere. “I chose Larry as my father! I willingly chose this man who had such a complicated psyche, and had in him a kind of repressed violence, and yet could paint so beautifully, and could be so generous.”

To Legere, Rivers’s sexual appetite—voracious, omni-directed—was part of his charm. “He met my mother and went crazy wanting to fuck her! For months he was saying, ‘Her neck is so beautiful.’ He wanted to fuck everyone in my family. He wanted to possess the whole gene pool! Almost like a god would!”

For the final session of Growing, Rivers put two monitors on a table that showed footage from the previous years, and had Gwynne and Emma, around 17 and 15, react to it. Again they were topless. Assisting now was a young, lanky Oregonian named John Duyck, who had wandered into a one-night job as a bartender at one of Rivers’s wilder parties—the Rolling Stones were among the guests—and ended up as his full-time man Friday. After Rivers’s death, Duyck would become co-executor of his estate—and very much an object, along with David Joel, of Emma’s discontent. When the controversy hit the papers, last summer, Duyck dusted off the foundation’s copy of Growing to see if he’d misremembered it.

“My memory from 20 years ago was that Larry came across as a caring, loving father,” Duyck says in a still-pronounced Oregon drawl. “So I watched it again. I had the same impression. It’s quirky, bad parenting, pushing the envelope, not great judgment, but you don’t get the impression that he’s anything less than caring, exploring, as an artist, talking to them as adults.”

As the film opens, Duyck relates, Rivers is working on the painting that came directly out of the filming, The Continuing Interest in Abstract Art: From Photos of Gwynne and Emma Rivers.Various stills from the footage have been sewn into the canvas—a process Rivers occasionally employed. Images that show the girls dressed are left as they are; those that show them topless or nude have been painted over, the private parts covered.

When, on her daughters’ behalf, Clarice prohibited the film’s showing at the Marlborough Gallery, Rivers was shocked, Daria Deshuk recalls. “He felt insulted that his children didn’t appreciate he’d been an artist his whole life, and that as an artist he’d been able to support his children, and wives, and his mother.” He told Emma, she recalls, that if he were a farmer, she’d be expected to help with the chores. Why should it be any different when the family business was art?

“I never really got what I wanted for this tape, which is the meaning of breasts in a girl’s life,” Rivers wrote in an essay on Growing for a 1985 book called Scopophilia: The Love of Looking, a collection devoted to voyeurism. “Maybe they just couldn’t verbalize what they felt, or maybe they didn’t even realize what I was attempting to accomplish. They were innocent. I couldn’t pierce that.”

Misguided as his aims may have been, say friends of Rivers’s, shouldn’t Growing be judged in the context of its more permissive times? From Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita to Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg’s Candy, the sensual allure of teenage girls was celebrated in the popular culture of the 1970s.

“I think that Larry was an artist even as a father, looking at everything in terms of revealing the human aspect, and trying to capture that,” suggests Nile Southern, son of Terry, and a close friend of Rivers’s. Daria Deshuk recalls Rivers actually saying, about Growing, “I’ve been making art all my life—why would you think this was anything else?”

Emma will have none of it.

“I don’t believe my father’s interests have much to do with his being an artist,” she writes. “There are many like him who never drew a circle. His own father was a plumber.… It’s known in our family that this plumber was coming on to the young girls my father brought home to meet his folks. So, I don’t link my father’s sexual interest in young girls to art. It’s simply that when pedophile-types have their own kids, they can abuse their unique position and get away with things they couldn’t otherwise.”

“My grandfather was not a pedophile,” Steven Rivers replies. “I never heard anything about him molesting anyone. He had an eye for cute girls but that could be applied to a lot of people.” Joan Gordon allows that her father could occasionally indulge in what might now be called inappropriate behavior, “a bit over the line.” But she agrees Emma’s version is an exaggeration. “So Emma is saying that because my father did this, his son became both an artist and a pedophile? Well, I think he was probably a little of both.”

As young adults, both girls struggled to find their way. Some of Gwynne’s happiest moments came in singing with her father’s jazz band, but in later years he would nudge her off the stage after a song or two and put Phoebe, the band’s singer, in the limelight instead. With doubts planted about her singing voice, Gwynne switched to acting, in college theater and summer stock, but she found the rejections especially painful. “It felt as if I were being judged not just as an actress but physically, and that felt familiar and awful somehow.”

She gave up acting and worked as a publicist; after a number of troubled romances, she married, at 37, a venture capitalist named Robert Cochran. At her wedding, in February 2002, she and her father performed together. Today his madcap world seems far behind her—she even runs a Sunday school.

Emma had a rougher time of it. Her anorexia as a teenager was serious enough to send her weight plummeting to 85 pounds and require treatment at a live-in therapy center. After attending Columbia and the New School for Social Research, Emma became an artist herself.

In the early 1990s, Emma staged an art installation at Peter Marcelle’s gallery that addressedGrowing with brutal directness. A hand-painted sign announced, FOR THE FIRST INSTALLMENT IN THE SIX-YEAR VIDEO SERIES FATHER MADE OF OUR BREASTS GROWING, SISTER SANG “YESTERDAY” IN HIS SHOWER. Inside the first of three rooms was a wire-mesh figure of Rivers, but its head was a video camera, with small stills from Growingpasted on the camera’s side. A wire from the camera went down through his body and out his groin, across to the opposite wall. It ended in a microphone that a wire-mesh Gwynne figure held. But the figure was headless. Its head was encased in a nearby TV screen with plastic over it, screaming rather than singing. “On the other side,” Emma explains in an e-mail, “the figure of my mother is against one wall, being held there by male hands and rope, while my figure has her back to my mother’s figure and is kneeling down throwing up into a toilet.”

A first marriage for Emma, at 23, ended quickly. For her second husband, she chose her father’s fitness trainer, 20 years her senior. “My father wasn’t very happy,” Emma admits in an e-mail, “but that was part of my kick.”

Critically neglected, Larry Rivers spent the 90s selling his new style of cartoony, three-dimensional artworks to the nouveaux riches, principally in New York and Palm Beach. His heroin-dabbling days long behind him, he lifted weights and juggled his on-again, off-again lovers. A young poetess, Jeni Olin, was in residence during the last five years of his life. Deshuk was still around, ensconced with Sam in a Bridgehampton studio paid for by Rivers. Clarice was in nearby Watermill, also in a Rivers-subsidized home. Sheila Lanham still visited: “I’d be coming out on the train to Southampton while he was putting another girl on the train back to the city,” she says with a laugh.

After an opening at the Corcoran Gallery in May 2002, Rivers fell ill. A hypochondriac, he’d feared his heart would fail. But no: the diagnosis was an advanced case of liver cancer. “From then on,” says David Joel, “it was me, John [Duyck], and Jeni Olin” tending to Rivers in his Southampton house. The tricky part was that Rivers didn’t want his family there: not his wives and lovers, not his children either. Both Joel and Duyck protested the policy. “We said, ‘It’s not fair to your family—or to us,’ ” Joel recalls. Why no family visits? “He said, ‘I don’t want to have to perform.’ ”

As Rivers’s condition worsened, Joel and Duyck did arrange for loved ones to come in half-hour slots, and for old friends to say good-bye. One day when Barbara Goldsmith was there with Cornelia Foss, Rivers told them to go see what he’d been working on in his studio. “There was a large painting … really a drawing, done from a photograph, of Clarice and the girls,” Foss recalls. “I said, ‘Larry, it’s one of the most beautiful paintings you’ve ever done.’ ” Jane Freilicher remembers it was in charcoal. “He had been working on it when he got ill—a tender, touching work. He was devoted to those two girls.” On another day, when Clarice and the daughters were there in person, Rivers looked at them and said, “This is what it’s all about—family.” Gwynne was touched, though not quite persuaded. “That was the only time he would have said that,” she says.

“If that whole end of the affair had been different,” suggests one close family friend, “and the kids had been allowed to be around their dad, they could have come to terms. I think that’s what’s at the heart of things.”

No one disputed the will, which divided Rivers’s assets and future art sales equally among his five children. (Clarice, the widow of record, and Daria, mother of Sam, were already taken care of in separate arrangements. Rivers’s first wife, Augusta, living quietly in Yonkers, was left a small sum.) But why were none of the “girls,” as Clarice likes to refer to her daughters and herself, put on the Rivers Foundation board, headed up by David Joel? “Emma wanted to be on the board after her father died,” says one board member, “and we wouldn’t let her—she was too angry.” And why was one of the girls not made a co-executor of the estate, along with Joan Gordon, instead of John Duyck? “The older boys understood,” says Duyck. “They said, ‘Why not? You know more about him as an artist—his dealers, his market—than we do.’ But Emma felt slighted.”

Duyck says he and Joel offered the daughters various heirlooms. At the time no mention was made by either daughter of Growing. It simply never came up. In 2005, Emma asked to come to the archives in Bridgehampton, and arrived with dealer Peter Marcelle, who asked a lot of questions and seemed, to Joel, unsatisfied by the answers he got. Emma said that she’d heard works of her father’s might be getting sold covertly by the estate—which was to say Duyck.

“It was far more innocent on my part than accusing anyone of anything,” Emma writes. She says she merely heard, from Marcelle, that another dealer had acquired Rivers works from the estate over the previous year. “I didn’t know if this was legit or not. Maybe John was passing the sales on to us?” (Joel says he spent years trying to account for, and retrieve, Rivers’s work at various galleries. That, he says, may have been the traffic Emma heard about.) After a “desist and whatever they call it” letter from Rivers-estate lawyer Ralph Lerner and a “barrage of angry phone calls from my aunt and Steven,” recalls Emma, “I shut up.”

Emma made no mention of Growing to the board for three more years, until the notion of the archive sale to N.Y.U. first arose. Joel says that when she did, she voiced no objections to his suggestion that tight restrictions be put upon it. (“There was no consent on my part,” Emma insists.) One member of the clan wonders if Growing is just the means she finally seized on to blow up her father’s reputation, as if, in some Greek tragedy, the only way she can rid herself of her demons is by killing him herself.

Emma disagrees. She says she’s actually quite happy these days. Last year, she married a third time, escorted down the aisle by a beaming Rainer von Hessen. Sergio Tamburlini, who works on behalf of Italian tourism, is, as Emma puts it, “a supportive, loving, and rightfully outraged husband.” For Emma, the destruction of the film is an uncomplicated issue: “I simply want the filmed record of substantial humiliation at my father’s hands, when I was a child, to be unseen any more,” she writes. “Is that too much to ask?”

‘As Emma’s aunt,” says Joan Gordon, “I would like to meet her in her house and simply ask her what she wants to resolve this.” But if Emma demands nothing less than destroying the film, then her siblings, from whom Emma is now estranged, say no way.

“My first opinion,” says Joseph Rivers, “was if this is going to make Emma happy to have the videotape, then give it to her. I personally don’t think that Emma is going to be any less distraught in life whether she gets the videotape or not, but that’s not for me to say, so give it to her.” He flashes a lopsided grin. “My second opinion? Fuck it—keep it.”

Steven and Sam agree—at least that the film should not be destroyed. “My sisters’ feelings are very important to me,” Sam says, “and so I hope we can come to an agreement that’s calming to them. But I do feel it’s ultimately art, and should be preserved, at least in part. And I think that destroying it completely would be tantamount to book-burning.” And in that, they have a surprising ally. “It may sound strange,” says Gwynne, “but the notion of burning my own image as a child is kind of horrifying to me.” She’d like the tape to be handed over from the foundation to her and her sister—not to destroy right away but to see and process, for the first time, as grown-ups.

How the hubbub over Growing will affect the market for Rivers’s work is a question most in the clan have pondered. By 2007, the Rivers estate and the I.R.S. agreed on the value of Rivers’s remaining 635 artworks. The tax bill was so large that the estate applied for an extension to pay over a 14-year period, with interest. “Which is a good thing if the art goes up in value,” notes Ralph Lerner. Unfortunately, the number was agreed upon before the stock-market slide. “It does suggest that the art market better go up,” says Lerner, “or the kids will have a harder time paying taxes.” Recently, one of Rivers’s major Civil War veteran paintings sold in the $1.5 million range to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Now will talk of child pornography turn off buyers? Or just stir the publicity pot and make Rivers a hotter name?

“As provocative as this current situation is,” says Joel, “the truth is that there is nothing more provocative, sensational, or more intriguing than Rivers’s work. It’s the work that Rivers did that sparked these dialogues and will continue to, for generations to come, because he set it up that way.”

If he were alive, Gwynne muses of her father, “I think he’d be defending himself. He’d say, ‘When I did this with you as a kid, I thought it would be interesting.’ ” At the same time, she guesses, “I think he would be pretty amused that, at 86, he’d be generating this much attention.”