All The Best Victims

holden steinberg

The shocking thing about Kenneth Starr’s alleged Ponzi scheme wasn’t the amount—$59 million, pocket change by Madoff standards—but his client list. How did an accountant from the Bronx pull in the likes of Bunny Mellon, Barbara Walters, Al Pacino, Caroline Kennedy, and Matt Lauer? And was it his obsession with his pole-dancing fourth wife, Diane, that drove him? The author follows Starr’s trail, to such spots as Harry Cipriani’s, the Four Seasons, and Herbert Allen’s Sun Valley retreat.

Two days before his arrest for allegedly cheating clients out of $59 million, financial adviser Kenneth Starr presided at one of Harry Cipriani’s coveted front-room tables, with a view of the Plaza and Central Park, and grinned when his wife, Diane, protested, not very seriously, that she’d thought their third-anniversary dinner would be a private affair.

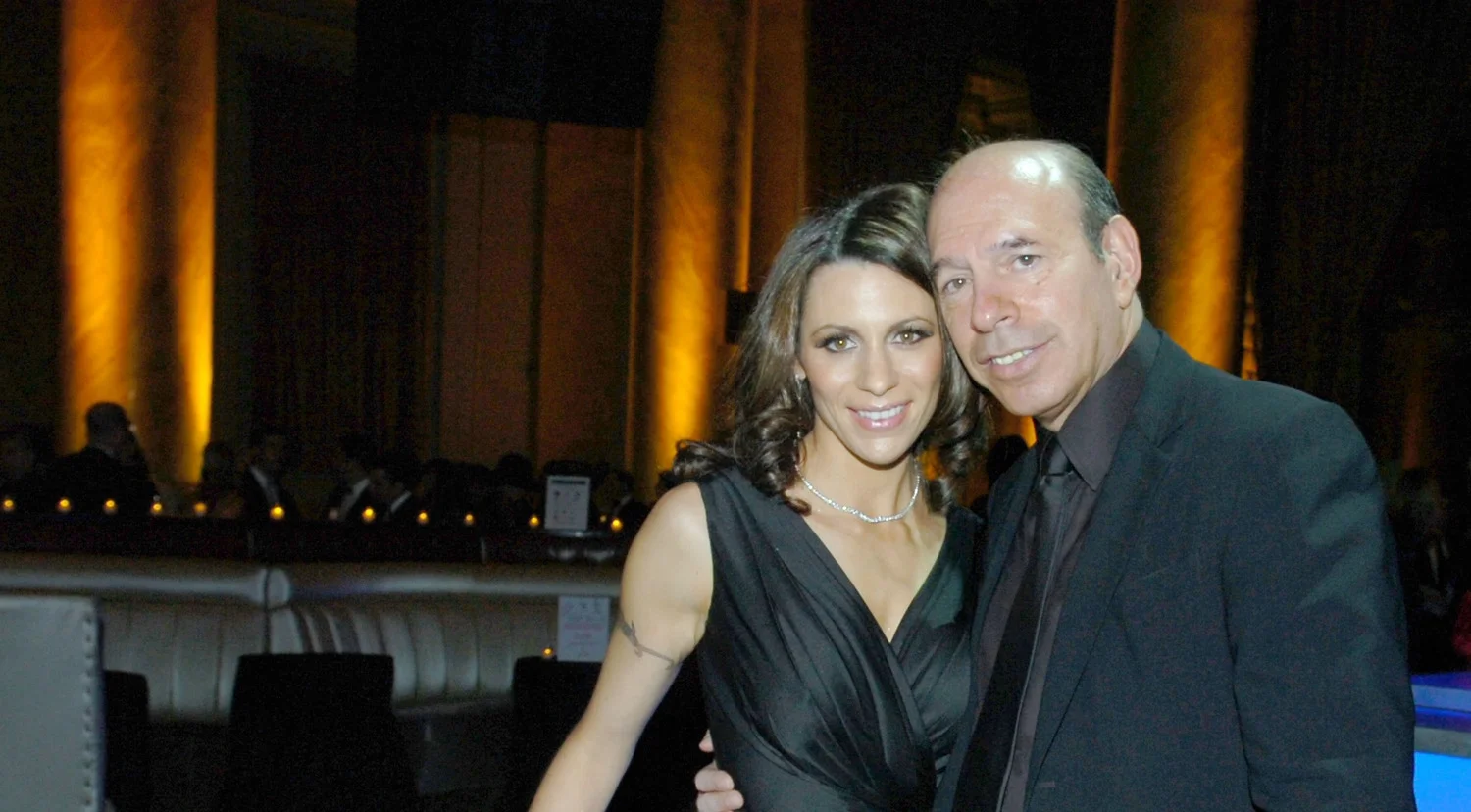

Diane Passage, 34, was wearing a black Gucci dress with a scoop neck that kept slipping to expose more of her Brobdingnagian breasts than the designer had intended—only when she got home would she realize she had it on backward—but Starr, 66, was proud of his fourth wife’s provocative figure. He liked to brag about her pole-dancing prowess. Only when she brought up her past employment as a dancer at Scores strip club did he wince. Why, though? she would ask him. She had nothing to hide.

Starr seemed happy that night, or so thought Jim Wiatt, former chairman of the William Morris Agency and a Starr client, who had stopped by for dessert. The two men, longtime friends, agreed to meet the next night for a drink at the Regency Hotel—and they did, Starr ordering his customary Diet Coke.

As the story broke, Wiatt would play and replay in his mind the scene at the bar. How could Starr have looked him in the eye—sympathizing, joking—only weeks after allegedly stealing $1 million from the account he and his wife had turned over to the great Ken Starr to manage?

By then, armed federal agents had made a 6:30 A.M. entry into the small lobby of 433 East 74th Street, a new, seven-story, glass-walled, luxury condominium. As one building resident told it, the doorman’s eyes widened. “Madoff?”

He meant Andrew Madoff, the younger son of epic Ponzi schemer Bernard Madoff. Andrew had moved, not long before, into an apartment upstairs.

“No,” one of the agents said. “Starr.”

The doorman rang Apartment 1-C, the triplex with the pool and l,500-square-foot garden. Diane says she awoke to hear her husband saying into the phone to the doorman, “Tell them I’m not home, but my wife is.”

The agents went away. Diane went downstairs to get breakfast for her 12-year-old son, Jordan. While he ate, she went back up to the bedroom to hear Starr start muttering about legal problems. Diane had never heard him talk like that before. He was always so upbeat.

An hour later there was a banging on the apartment door. Starr looked sick. “Say I’m not home,” Diane says he told her.

She opened the door to six federal agents. “Ken’s not home,” she said dutifully. The agents showed her a warrant and came in anyway.

After the agents asked her a second time if Starr was home, the largest of them, a giant, leaned over and said in a low, serious voice, “I’m going to ask you one more time.” Diane recalled how in the movies people got arrested for lying to the F.B.I. That was when she whispered, “He’s in the bedroom closet,” and the agents went up to find a telltale pair of shoes protruding from beneath the hanging clothes.

When the agents left with her husband sandwiched between them, Diane called a friend. What should she do? “Keep your son home from school and don’t talk to anyone until you have a lawyer.” So Jordan stayed home with his mother in the $7.5 million apartment they’d moved into just one month before, its big, boxy rooms still empty enough that their voices echoed, while Starr was hustled downtown to a cell at the Metropolitan Correction Center, on charges of fraud and money-laundering that could bring him a sentence of up to 45 years.

There Starr (no relation to the special prosecutor who tormented President Clinton) remains—a flight risk, his assets frozen, his bail requests denied—while, on a June evening, Diane orders a Bacardi and Coke at Ballato’s, an Italian restaurant on Manhattan’s Houston Street, and tries to make sense of it all. She knew nothing about Starr’s business, she says. The charges are news to her. “I hope and pray that this will all be a big mistake that will go away,” she says.

All-Starr Cast

In sheer numbers, Starr’s alleged Ponzi scheme pales beside Madoff’s $65 billion, and in person, wearing a black silk shirt or zip-up designer sweats, Starr must have seemed a little cheesy compared with Madoff, who favored Savile Row suits and crisp white shirts. But in one regard, Starr had Madoff beat: his clients were far more dazzling.

A handful of the names have trickled out since Starr’s arrest: director Mike Nichols and his news-anchor wife, Diane Sawyer; The View’s Barbara Walters; writer-director Nora Ephron and her husband, author and scriptwriter Nick Pileggi. But these are just a few in a daisy chain that winds from New York media to Hollywood and back, in which one boldfaced name recommended him to another.

Photographer Annie Leibovitz came in partly because photographer Richard Avedon had been a client. Columnist Liz Smith came aboard in part because Time Warner heiress Courtney Sale Ross was a client. Nichols and Sawyer were part of that circle, as were U.S. State Department heavy Richard Holbrooke and his wife, writer Kati Marton; author Ken Auletta and his wife, literary agent Binky Urban; journalist David Halberstam; and veteran publisher Joe Armstrong. All were or had been Starr clients. Who was the lure for bringing in news anchors Tom Brokaw and Matt Lauer, and the late Walter Cronkite? Or sportscaster Frank Gifford and his wife, television hostess Kathie Lee? Or NBC chief Jeff Zucker and his wife, Karen? Who could say for sure, but what TV heavyweight wouldn’t want to join a club that had luminaries like those as members?

On and on it went: from Hollywood producers Scott Rudin and Ron Howard to Broadway’s Neil Simon and Gene Saks. Movie directors Jonathan Demme, Sam Mendes, and Doug Liman, actors Liam Neeson, Al Pacino, Warren Beatty, and Candice Bergen, political satirist Michael Moore, singer-songwriters Paul Simon and Carly Simon, fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi—all were clients. Former Citibank chairman Donald Marron and Sony chairman Howard Stringer—clients, both of them. Even Caroline Kennedy was a client. Some just had Starr do their taxes and pay their bills. (Vanity Fair editor in chief Graydon Carter was in this camp.) But many had let Starr talk them into giving him their money to invest.

In the Grill Room at the Four Seasons, Starr would awe a new prospect by dropping two of the weightiest names in his stable: retired Blackstone Group chairman Peter G. Peterson and Bunny Mellon (the nonagenarian widow of philanthropist Paul Mellon), who was in elegant seclusion on her vast Virginia ranch, as close to a queen as might be found in America. “Just ask Pete about me,” he’d say, and if the prospect took Starr up on that suggestion, Peterson would sing his praises. So, for a long time, would almost any of Starr’s other clients, for Starr had done more than name-drop to build his clientele. He was a great accountant and a shrewd investor: a lot of his clients had made a lot of money—for a while.

“I had nothing but good relations with him,” says Sotheby’s Jamie Niven. “I never experienced the side of him that people are talking about.”

Only now has it become apparent that Starr was allegedly putting millions of dollars of certain clients’ money into high-risk investments, from South American electronic voting machines to lizardy “lounge clubs”—many of them companies which, according to the indictment, Starr or his associates had financial interests in.

One of Starr’s associates was Andrew Stein, the ex—Manhattan borough president who’d struggled in recent years to make a new career out of his old political connections. While his ex-wife Lynn Forester went off to make more than $100 million in cell-phone licenses and marry a Rothschild, Stein gave intimate soirées for friends like Shirley MacLaine, Barbara Walters, and Warren Beatty and Annette Bening, and hoped that the Wall Streeters he put in the mix might throw him a bone. He came close—almost co-founding a hedge fund, Stein says—but nothing really panned out, the bills piled up, and he fell woefully behind on his taxes. Prosecutors allege Starr paid Stein as a social facilitator through a shell company and Stein failed to declare $2.1 million in earnings to the I.R.S. To a lot of New Yorkers, the news of Stein’s arrest, on the same day as Starr’s, for tax evasion, was even more shocking. True, Stein had always seemed clueless about his finances: according to the New York Post, his own brother, Jimmy Finkelstein, has sued him for nonpayment of a $100,000 loan. But to end up like this? Astonishing.

Those who’d admired Starr’s rough savvy were left to wonder: why steal when, as it was, Starr & Co. managed $1.2 billion, at fees of 1 to 2 percent? Like a Greek chorus, his shocked clients pointed as one to the lavishly endowed Diane, for whom, the indictment notes, Starr purchased more than $400,000 of jewelry from bling jeweler to the rap world Jacob Arabo. “When your business manager marries a stripper,” says one rueful client, “that’s a tell.”

Diane did like to shop, as many of her Facebook status updates reportedly attest. (“Just got my pink diamond Detroit D from Johnny Dang!!! Amazing!!!!”) And her rise from stripper to richly kept wife does largely align with the chronology of crimes detailed in the indictment. But in person Diane comes across as anything but calculating. And the story she tells, as her chicken parmigiana sits untouched before her, is so revealing that it makes her seem guileless—no gold digger would tell it.

A previous version of this article erroneously named Martha Stewart as one of Starr’s clients.

Diane and another dancer were approached at Scores, in Midtown Manhattan, one night in late 2004, she recounts, by a middle-aged couple enjoying a racy night out. Next thing they knew, Ken and Marisa Starr invited them to dinner. The dancers agreed—for $1,000 each—as long as dinner was the only thing on the menu. Soon thereafter the Starrs took them to the Four Seasons, Diane recalls, then to Bouley, then to Per Se: $1,000 for each dancer, each evening. (Marisa says she played no part in any such financial arrangements, and merely allowed Ken to take Diane to social events because her own declining health kept her increasingly housebound.)

For nearly a year, Diane relates, the $1,000 dinner dates continued, though now just à deux: Ken and Diane. Oddly, says Diane, Marisa set up almost all the dates; she was in control. But Diane exercised a control of her own. “During that whole year and into early the next year,” she says, “I never had sex with Ken.”

Only when Starr moved to the Regency Hotel did Diane begin staying overnight with him, she says, while the Starrs negotiated their separation. She would have been happy, she says, to have Starr merely support her and her son. According to Diane, it was he who insisted on giving her a huge engagement ring, the Las Vegas wedding, the jewels and designer clothes. And it was he, she says, who pushed to buy a large, new apartment. “I had never owned anything in my life,” Diane says quietly, “so Ken said, ‘Let’s buy a condo.’ It was my dream place. Now it’s become a nightmare.”

Diane says she had no idea how Starr was financing the condominium maisonette he bought last April. Prosecutors claim they know. They say Starr went from channeling client money into risky investments to stealing $7.5 million outright. He is accused of taking $1 million from the account of actress Uma Thurman, who had been a friend since she was 17. When she found out, Thurman stormed into his office with lawyers in tow, to be met with lame excuses. When those fell flat, Starr reimbursed her—by allegedly taking $1 million from Jim and Elizabeth Wiatt’s account. Another $5 million was allegedly purloined from the account of Bunny Mellon. “I asked him what that was for,” says Mellon’s lawyer, Alexander Forger, who says he discovered the $5 million withdrawal a few weeks later. Starr said it was for a new HBS bond fund. “I suggested I would rather have it back in Treasuries,” Forger recalls dryly. But the money failed to reappear.

Diane may have been one reason Starr’s spending and alleged larceny seemingly expanded as it did, but the history of his suspect financial dealings goes back years before he walked into Scores. Actor Al Pacino may be out many millions, the result of alleged mishandling that goes back at least to 2001. As for Jane Hitchcock, mystery novelist and woman-about-town in New York and Washington, she’s convinced that Starr began plundering the $70 million estate of her mother, radio star Joan Stanton, in 1994, suggesting Starr was a master con man at work long before Diane Passage ever shimmied up a pole.

“A story he would tell was that he was at Courtney Ross’s wedding in Italy,” recalls one former business colleague of Starr’s. Courtney, the widow of Time Warner C.E.O. Steve Ross, who had bequeathed her a fortune of some $800 million, was marrying Swedish businessman Anders Holst in Florence in 2000. “Someone wanted to take a picture of this group who just happened to be all Ken’s clients. And he said, ‘Sure, I’ll be in the picture.’ And one of these people said, ‘Why do you want him in the picture? He’s just the accountant.’”

Adds the former colleague: “I took from that story that he was very resentful, that he felt that wasn’t enough and he had made these people lots and lots of money, and what had he gotten in return? Mere thousands of dollars in accounting fees, and ‘Thanks.’ Perhaps he felt that wasn’t enough and he was entitled to be in this world of multi-millionaires, too.”

Unlike Bernie Madoff, Starr never engaged in the wholesale defrauding of all his clients. From the start, it seems he picked and chose. He treated many clients well right up until his arrest. Those he treated badly must have been left wondering: Why them?

Eager to Please

Starr loved to tell another story, this one about Paul Mellon, who was supposedly so indignant at his own accountant that he asked a florist in a Manhattan shop, “Who do you use as your accountant?”

“Ken Starr,” spluttered the florist. And so, overnight, the life of the Bronx-born Kenneth Ira Starr changed.

Alexander Forger, Bunny Mellon’s exclusive lawyer, says he doubts that story. Paul Mellon, he points out, had platoons of professionals. But that, insists a former business colleague of Starr’s, is how Starr told it. And this much was indisputable: Starr did start working for Mellon, and the Mellon connection made his career.

The son of a public-school principal, Starr grew up on College Avenue, in the South Bronx, beside a cluster of housing projects. Very bright, he entered Queens College at age 15. Eventually he married his college sweetheart, Gail, who bore him two children, a son and daughter, Ronald and Terri. For a while he worked at a Manhattan accounting firm. But when he landed Mellon, he struck out on his own.

A house in the Hamptons led Starr to his first Broadway and Hollywood clients. Librettist Peter Stone (the musical 1776), a great wit, took his new accountant to a fancy Italian restaurant one night. Starr, still a boy from the Bronx at heart, perused the script menu in bafflement. “I’ll have spaghetti and meatballs,” he said at last, “and a glass of milk.”

Stone roared at that, but he admired Starr’s acumen and talked him up to humorist Art Buchwald, actress Lauren Bacall, writer Robert Benton, director Sidney Lumet, and others. All became clients. “Ken suggested that taking care of your money was time-consuming,” says one Hamptons client. “And because you were such a high earner, you shouldn’t be wasting your little head about this.” Starr would tell some of them how much they could spend for the year, as if they were children, then pay their bills and invest the rest—some of it in special funds he described as open only to the Mellons. “He could link my paltry dollars to their zillions,” recalls publicist Leslie Dart. But, she adds, “that never did happen.”

Voluble enough to flummox the artists with financial jargon, Starr at the same time stoked their dreams. “Truthfully?” Starr would say. “Honestly? Candidly?” He’d let those three words roll out one after another, letting the suspense build while some quivering playwright awaited the verdict with baited breath: Yes, the playwright could afford that shiny new car. “He was the most optimistic person I have ever encountered,” says Kati Marton. “Every single one of my fantasies, he encouraged. ‘Go ahead and buy that pied-à-terre in Paris. The place on the beach in the Hamptons? We’ll be able to afford it.’ That was part of his charm.”

Starr loved his creative clients—he invested his own money in more than one Broadway show, and adored lunching with Art Buchwald, who reportedly came to refer to Starr as his best friend. But the ones Starr focused on were the ones with the most money, and aside from Paul Mellon, several were women on their own. Courtney Sale Ross, newly widowed, became a client. So did Louisa Sarofim, Houston philanthropist and heiress to the Brown & Root engineering fortune. Each had other advisers to keep an eye on their money. But not Joan Stanton, whose late husband, Arthur, had built the family fortune by introducing the Volkswagen Beetle to the U.S. How Starr flattered her, while allegedly keeping her in the dark and intimidating her children, is a chilling tale.

In her youth, Joan Stanton (neé Alexander) had been the radio voice of Lois Lane and Perry Mason’s secretary, Della Street. In later life she presided over a glittering salon at 10 Gracie Square, and another at her classic, shingle-style East Hampton mansion on Hither Lane. She was a commanding figure in every sense but one: she had no clue how to handle her money.

Arthur Stanton had sought to protect her by leaving his estate in the care of two men: Starr and the family lawyer from Milbank Tweed. But when the lawyer decamped from the firm in 1994, Starr became the sole overseer. That, say Joan’s children, Timmy, 51, and Jane, 62, was when the trouble began.

The children were charming and smart, and Jane had had triumphs as a playwright and novelist, but they’d had a pampered life, and a brother, Adam, had died of a drug overdose. Starr used that, the children came to feel, to undermine them. “We’ve got to rein them in,” Starr would cluck to their mother when he visited her, according to the children; certainly she shouldn’t share details of her finances with them. A prudent move, he suggested, was to create a trust that would pay Joan an annuity and then pass, upon its maturity after eight years, to the children tax-free. Part of the trust—some $5 million—Starr put in something called the Blackstone Investors Partnership. Or so the children were told, in a whisper, by their mother.

Pete Peterson, co-founder of Blackstone, had no reason to think Starr was anything but good news. Peterson had heard close friends rave about him—Diane Sawyer, Mike Nichols, and Barbara Walters, among others—and when he checked out Starr & Co., all the signs were good. Starr seemed to want nothing but to throw millions of his clients’ dollars into Blackstone funds. Blackstone dealt in bigger chunks than that, from institutions, not individuals, but by pooling a few million from one account, a few from another, Starr could hand over a pot of capital that Blackstone was happy to invest—about $110 million in all.

Only after Starr’s arrest would Peterson wonder about the return flow of profits. Since Starr was the sole contact for those “aggregator” funds, the profits went to him, to be distributed, in turn, to his clients. Peterson had no idea how much of that return flow Starr kept. Nor did he know, until after the arrest, that Starr had allegedly used the Blackstone name for those self-created funds.

By the late 1990s, Starr was lunching regularly with Peterson at the Grill Room, talking up deals. The dot-com bubble was swelling, and so when Starr proposed that the two start a high-tech venture fund together in 2000, Peterson signed on.

Millennium Technology Ventures had nothing to do with Blackstone. It was Starr’s baby, set up near his new office, at 850 Third Avenue, so he could shuttle between offices. But Peterson did become an advisory partner. In that giddy time, Millennium raised $160 million, half in cash and half in future commitments. Most of the 60 investors were Starr clients, whom he imbued with great expectations. “He would tell his clients how terrific all these investments would be,” says one person close to Starr at the time, sighing. “Everything was always going to the moon with Ken.”

And so they were a bitter bunch when the dot-com bubble burst and the fund retrenched, in 2002, after $60 million had been spent and largely lost. On paper, music executive Tommy Mottola lost about $3 million. Entertainment lawyers Alan Grubman and Bert Fields reportedly both incurred six-figure losses, as did director Martin Scorsese and a host of others. “That,” says one disillusioned investor about Starr, “is when I figured out he was full of shit.”

In fact, the fund had a 10-year life, and has since done much better, so the investors who were locked in have seen their losses lessen over time. Starr was marginalized after 2002, says a Millennium principal. But he was listed as a special limited advisory partner until February 2008. Peterson remains a special advisory partner still. His old friend’s arrest has him wondering how he misjudged the man so badly. “Has he always been kind of pathological?” Peterson asks sadly. “And was he simply buttering people up and building relationships, but ultimately he was always a pathological case? Or did something in the way of a profound midlife crisis trigger this behavior?”

On the Sly

Starr had another setback at this time, one that might have broken a less ebullient character. Sylvester Stallone, believing he had been defrauded of $10 million, sued him.

It was a sordid story. In the late 1990s, as the Planet Hollywood restaurant chain teetered on the verge of bankruptcy, Stallone claimed Starr persuaded him not to sell his $10 million in stock. At the same time, Planet Hollywood founder Keith Barish, another Starr client, was selling. The terms of the out-of-court settlement remain private, though Stallone’s lawyer called them “substantial” at the time.

The Stallone settlement may have been the financial hit from which Starr never really recovered. Certainly it may have contributed to him losing at least one major client: Courtney Ross, who’d also invested in Planet Hollywood, says an associate. So powerful was his spell, though, that other clients seemed to ignore the news, even other actors, none more so than Al Pacino.

For Pacino, Starr was like a brother in an extended family that included Sidney Lumet, director ofSerpico; Marty Bregman, producer of Scarface; and Anna Strasberg, daughter of fabled acting coach Lee Strasberg. All had become Starr clients. But for actress Beverly D’Angelo, who took up with Pacino in the mid-90s, Starr came to seem more like a brother-in-law from hell.

D’Angelo didn’t realize what she was up against until her twins were born in 2001. The actress was down to her last $350,000, so Pacino agreed to pay for all baby-related expenses. All D’Angelo had to do was pay up front and submit the receipts to Starr.

D’Angelo says some of the reimbursements came late. The rest came not at all.

When she complained to Starr, she says, he told her she was spending too much. “You don’t know what you’re talking about,” D’Angelo recalls telling him.

“Yes I do,” Starr said in a taunting tone, she says. “Yes I do, yes I do … ”

As tensions deepened, D’Angelo says, she warned Pacino that Starr might be mishandling his finances, too. Why not have his account audited? Pacino refused. After several of these back-and-forths, the couple broke up. To friends D’Angelo said she blamed Starr. He’d wanted her out of Pacino’s life, she felt, and at last he’d had his way.

In the court battle that followed, both parties had to submit financial disclosures. D’Angelo learned that Starr was the executor of Pacino’s estate. She also learned that Pacino had a net worth of $60 million in 2001 and had since made millions more. The custody battle was settled, and the separated parents proceeded to raise their twins in a fairly harmonious way—until the end of 2009, when Pacino e-mailed D’Angelo to say that he had a financial crisis on his hands. Somehow, according to Starr, his net worth was now less than $48 million. Maybe much less.

A Pacino lawyer followed up to tell D’Angelo that child support would have to be cut. Both she and Pacino would have to reduce their spending dramatically. For starters, the lawyer noted, there was a 2009 charge of $123,000 on a credit card issued to D’Angelo, a card meant to be used for the twins’ medical care. The charge was from a store in the Los Angeles area called A Bundle of Convenience, which sold baby accessories and services, as well as fruit and gift baskets.

D’Angelo remembered stopping in the store once to buy a small quantity of baby formula—in 2001. Mystified, she called the store. The woman she spoke with acknowledged that D’Angelo hadn’t purchased or shipped anything from the store in 2009. Not to worry, the woman said; she would call a person who worked at Starr & Co. in New York. How, D’Angelo wondered, did this woman know anyone at Starr & Co.?

Later that day, Peter Lev, the senior partner at Starr & Co. who handled Pacino’s account, called D’Angelo to say there’d been an oversight. The charge would be expunged. (Lev declined to comment.)

Not long after Starr’s arrest, D’Angelo says, she spoke with an assistant U.S. attorney handling the case, and related her Bundle of Convenience story.

“You’d be surprised,” he replied, “how much of that illegal activity we’re finding.” (A spokesperson for Pacino said that the matter is currently under investigation and it would be inappropriate to comment at this time.)

By this point Starr’s personal life was unraveling.

He’d shed his first wife, Gail, long ago, and later married his office manager, a meek if attractive woman named Sheila, who went on to hire another woman to replace her as office manager, who then replaced her as Ken’s wife. Marisa Vucci, recalls a family friend, was a tough Italian girl from 115th Street in East Harlem, cute and perky—and just two years older than Ken’s daughter Terri.

As office manager, Marisa, who has not been implicated in any wrongdoing, oversaw the fast-growing Starr & Co. even as she raised the couple’s two daughters. By 2004, though, she had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Starr “freaked out and left,” Marisa says, spending nights in the city while Marisa spent more and more time in the family’s large, contemporary house in Oyster Bay Cove. “We weren’t going to get divorced … but we could live separately,” Marisa says. “That seemed fine to me.”

But, in the spring of 2007, Starr made plans to wed Diane in Las Vegas.

Marisa’s departure as office manager seemed to slide Starr & Co. into a state of disarray. Tax returns languished, statements got delayed. Mike Nichols and Diane Sawyer peeled off, irked by the general sloppiness. Neil Simon was livid after learning that a trust set up for his grandchildren had been put in a non-interest-bearing checking account, according to someone close to Simon’s affairs. Starr seemed oblivious to it all. Squiring his ex-stripper wife around was his new fascination. According to the indictment, Starr put Diane together with ex—EMI and Artemis Records head Daniel Glass; the result was an ownership stake for Diane in Glassnote Records, paid for by Starr clients. Diane also earned around $100,000 for a year’s scouting, and brought in two bands that Glass signed. More client money is alleged to have been steered to movie producer Marty Bregman for a slate of independent films that was to include, with Diane’s participation, Desert Rose, based on Larry McMurtry’s novel about an aging stripper.

Even Starr, though, had a hard time persuading clients to put money into Pole Superstars, Diane’s vision of a national yearly event to promote pole dancing as a competitive, perhaps even an Olympic sport. Instead, Starr paid to stage pole-dancing evenings in New York clubs. “There was some talk about doing a TV show,” recalls one guest. “It never made a lot of sense.”

Unfazed, Starr talked up Diane’s pole-dancing plans at the annual Allen & Co. retreats, for corporate and political big shots, in Sun Valley, Idaho. “It’s fantastic exercise,” he told one table of guests as Diane nodded. “Do you want to see it?”

One of the guests said, cautiously, “I don’t see a pole anywhere.”

Starr whipped out his iPhone and showed Diane in action. “You should see my 15-year-old daughter do it,” he exclaimed.

Increasingly, money was the problem. “When he was with Marisa, based on the lifestyle, I would guess he had to have a $3 to $4 million income,” says one former Starr & Co. executive. “Then, with Diane, you need to double it. That’s a hard thing to do. It’s not that kind of business—it’s a service business. You’d have to become twice the size; you can’t just sell another 100,000 razors.”

The former executive said Starr began urging his senior partners to put their clients into truly dubious investments, ones he or a cohort had financial interests in. To some extent, whether clients got put into questionable investments depended on which senior manager oversaw their account.

Some were more pliable than others. Some had particularly pliable clients. Among those was Joan Stanton.

Bedridden by 2006, Stanton had her doubts about Starr now, say her children, but felt too afraid to confront him. The children were fearful, too. They worried he would talk their mother into cutting them out entirely. Only one person in the Stanton household wasn’t scared: Jim Fennell, the caretaker.

Fennell, a local East Hampton man, had devoted himself to the Stanton family for years, so much so that Joan had dared ask Starr to have him named a co-executor of her estate. In that capacity, Fennell started studying the sketchy portfolio statements Starr & Co. sent to Joan. The investments Starr had Stanton in—why were they just listed on Starr & Co. letterhead? Why wasn’t there any paper from the other firms to prove the money was there? Why was the overall value of the estate declining in a bull market?

Fennell’s suspicions deepened when Starr talked Joan into letting Starr take out a $5 million line of credit on her East Hampton house on Hither Lane. “Ken told me that Hither Lane wasn’t going up in value anymore,” Fennell recalls. “So he wanted to take $5 million out of the property and put it into another investment. ‘We’ll make a million dollars,’ he said to her,” Fennell recalls Starr telling Joan, “so she said O.K.” Nine months later, Fennell saw that a state tax bill of $750,000 was being paid, on Joan’s behalf, with a check from the $5 million credit line. “In fact, he was using the line of credit to pay bills,” Fennell says. “I said, ‘Mrs. Stanton, this stinks.’”

The next time Starr came to visit her mother at 10 Gracie Square, Jane made sure to be there. Fennell advised her to nod and listen, so she did, marveling as Starr launched into yet another pitch for another risky investment—so persuasive that even she was ready to shout “Yes!” As soon as Starr left, Jane asked to see the portfolio statement Starr had brought. “Mummy, this is ridiculous,” she said. “He could put any numbers he wants here.” She persuaded her mother to call a close friend whose own doubts about Starr had been planted long before. Joan hung up ashen-faced. “Am I broke?” she asked her daughter.

Joan got out her new will, the one that Jane says Starr had had drawn up for her. When Jane looked through a xeroxed copy that night, she gasped. Though it had been explained that her mother would be receiving, for her signature, a document granting Starr durable power of attorney in the event she became incapacitated, the letter Jane saw that night—the letter that she says had actually been sent—was very different. It granted Starr durable power of attorney—complete control over Joan’s finances—immediately. The letter bore Joan’s signature. Jane was horrified by the document—and so was her mother, who Jane says didn’t realize what she’d signed.

At last, Joan agreed to call in an outside lawyer. The lawyer went to Starr’s office and asked him why he’d awarded himself durable power of attorney. Starr allegedly denied having done it. The lawyer pulled the telltale letter from his briefcase. “What’s this, then?”

Betrayal of Trust

The full story, as Timmy and Jane recount it, was worse than anything they’d imagined. The trust was a sham. Starr had either blown the $8 million on risky investments or spent it; the money was gone. In 2000, when the trust terminated, Starr had simply taken millions from one of Joan’s liquid accounts and used them to cover the losses.

As for the investments, they were in either high-risk theatrical ventures—Paul Simon’s flop musical, Capeman, for one—or companies Starr and his associates had financial interests in. Among such associates was Keith Barish, the Planet Hollywood founder. About $4.5 million of Joan’s money had been put by Starr into Planet Hollywood for a dead loss. And what of the cryptically named NIS-II and KB-II, both run by Keith and his wife, Ann? Barish describes them as typical private-equity funds, holding capital for promising investments. But they were, as their own documents portrayed them, “speculative and high-risk,” hardly the sort of investments a nonagenarian should be making. Starr had transferred as much as $3 million of Joan’s money into the bank accounts of NIS-II and KB-II, according to the Stanton complaint. Joan had no idea, Jane says, that the funds were operated by the Barishes, whom she knew and disliked. Now that she did know, she started planning to sue.

Barish was an interesting case. In his early 20s he’d started an offshore fund called Gramco, from which he had made millions and filled an apartment at 740 Park Avenue with Monets and Giacomettis. He married Ann, whose closest girlfriend, starting in kindergarten at the Brearley School, was . . . Jane Stanton Hitchcock. Barish had gone on to produce major Hollywood hits like Sophie’s Choice before running into a wall with Planet Hollywood.

Hitchcock was as surprised as her mother to learn that the private-equity funds of her old friends Ann and Keith were recipients of millions of dollars of her mother’s money. She’d had no idea. According to the complaint, other Starr clients who had contributed to the Barishes’ NIS-II and KB-II funds, knowingly or unknowingly, included Louisa Sarofim, the Houston heiress, whose $20 million foundation Starr ran from 850 Third Avenue, and Neil Simon. Another big investor, along with Stanton, was Bunny Mellon.

In the years after he’d plucked Starr from obscurity, Paul Mellon had had no reason to question his protégé’s smarts or loyalty. Had he been able to follow Starr from beyond the grave, where he was put regrettably, in 1999, Mellon might have developed a different view.

Starr had visited Bunny at Oak Spring, her Virginia farm, admiring her 10,000-volume botanical library, along with the greenhouse and gardens. For her 90th birthday, he and Marisa went up to her place, where she greeted guests from a bed in a field of wildflowers. In return for her fondness and favor, Starr put millions of Bunny’s dollars into risky investments. One was Martini Park, a planned chain of nightclubs owned by one Christopher Barish—Keith’s son. Two clubs did open, one in Plano, Texas, and one in Chicago. But the chain quickly collapsed. (Chris Barish did not return calls for comment.)

High-risk at best, this was clearly another investment a 99-year-old woman should not be in. And yet Starr, who had Bunny Mellon’s power of attorney, had directed $6.5 million of her money into this and others.

At her children’s urging, Joan Stanton filed a civil suit against Starr in April 2008. Upon her death, a year later, at 94, her daughter went one step further: she laid out the particulars of the suit before a New York district attorney, who then chose to file a criminal case. After years as a lonely Cassandra, telling anyone who’d listen what she thought of Ken Starr, Jane Stanton was determined to see justice done. “Clearly, Ken never read any of my novels [Trick of the Eye, Social Crimes],” she says grimly. “If he did, he would have known that all I write about is revenge.” That case would morph into the May indictment that finally put Starr behind bars.

With Joan Stanton’s account closed to him now, Starr allegedly plundered others. Carly Simon says she grew alarmed in January 2009, when a Starr & Co. bookkeeper wrote her to ask that she transfer all the cash in her Martha’s Vineyard bank account to Starr & Co. so the firm could cover payroll. “All hell broke loose in my mind,” Simon says. She looked more closely at her recent statements. Millions of her dollars had been invested in companies she had never heard of—to what end?

“I still have no idea,” she says, “what happened to the money in those partnerships.” At the very least, she says, she lost several million dollars. Compared with Jacob and Angela Arabo, she got off easy.

Since Starr’s purchase of $400,000 in jewelry from Arabo for Diane, the rap world’s purveyor of fine stones had come, like Al Pacino, to view Starr “like a brother.” And so, when an unfortunate sequence of events led to Arabo’s conviction for laundering cash through jewelry sales to benefit the members of a narcotics conspiracy, he asked Starr to handle the family finances while he was in jail. According to the indictment, starting in February 2008, Starr handled them in spectacular fashion. Martini Park was a natural—$3 million of the Arabos’ money went there. Another surefire winner was Jinti, a Chinese Internet site. Starr reportedly had Pacino in it as well. As of July 2010, the projected value of Jinti was under a million dollars.

Then there was Universal Identification Solutions—the South American electronic-voting-machine company. The address for U.I.S. was 850 Third Avenue, 15th floor—the same as Starr & Co. Linked to it was a curious character named Gustavo Reyes-Zumeta, based in Virginia, who’d registered a patent for an “ornamental design” on the voting machines. Reyes-Zumeta had declared personal bankruptcy in 2005, and his lawyer for the process didn’t have good memories of him: “He claimed to have contracts to produce voting machines for South American companies,” recalls Thomas DeCaro. “He said he’d get a 600 percent return on a seven-figure investment. You’d lie awake dreaming of the money you’d make … the creditors were crawling all over him.”

Last year, Reyes-Zumeta, a Venezuelan whom his former lawyer describes as looking like a gaucho, reportedly surfaced in El Salvador on the day of the national elections. With the right-wing Arena Party’s longtime hold on the country threatened, he broadcast the election results, after U.I.S. had certified the viability of the electronic vote-counting system.

By November 6, 2009, Angela Arabo, the imprisoned jeweler’s wife, had become suspicious enough of Starr and his talk of windfall profits from the couple’s investment in U.I.S. to tape-record her conversations with him, excerpts of which are contained in the indictment. Reyes-Zumeta was getting checks that day, Starr assured Angela. Starr’s son Ron had “glued himself to” the shadowy Venezuelan to make sure the checks reached the bank, from which the money would flow to Angela.

Three days later, Starr reported a setback: Reyes-Zumeta had been in the hospital. Fortunately, Starr had been in touch with a Venezuelan official. “They’re just working out the final details as we speak.”

“But I thought [Reyes-Zumeta] had the checks already,” Angela said.

Absolutely, Starr assured her. “He just can’t deposit them until he gets word from the minister.”

And so it went, like a Marx Brothers movie, each excuse zanier than the one before. None of the promised riches came through. Instead, the Arabos lost, in all, $13.875 million. (Reyes-Zumeta declined to answer questions from Vanity Fair.)

Show Me the Money

By this time Starr’s world was crumbling. In the summer of 2009, Keith and Ann Barish reached a settlement with Jane Hitchcock in regard to the NIS-II and KB-II funds. The terms were undisclosed; Stanton lawyer Richard Bronstein acknowledges that the Barishes returned the money Joan Stanton had put into those funds at Starr’s behest. (Keith Barish says that a successful investment by the funds allowed him to redeem any investors who, like Stanton, wished to recoup their money, and that once the Stanton estate was reimbursed, the suit was dismissed without admission of wrongdoing.) Starr had to know that his own chances of evading a similar settlement had just diminished.

Also at this time, Alexander Forger demanded that Starr reimburse Bunny Mellon for the money put into risky investments; Starr sent him a check for $4.3 million. Other clients were taking closer looks at their accounts, and not liking what they found. According to the indictment, Neil Simon had learned that $4 million of his money had been put into Martini Park; his lawyers were demanding it back. Later, prosecutors would allege that Starr reimbursed him by taking the funds from at least three other clients: Jim Wiatt, Marty Bregman, and Denise Rich. Carly Simon’s lawyer, L.A. heavyweight Marty Singer, was demanding answers. The Arabos were telling what they knew to investigators. Beginning in July 2009, the S.E.C. had begun its own inspection of Starr & Co.’s books.

The beginning of the end came in January, when Starr reached a private settlement with the Stanton estate. A source close to the deal says Starr agreed to pay the estate $3 million; in view of his deepening financial straits, the estate agreed to six installments of $500,000 each, payable over 18 months. Starr managed to make the first two, but by the July 1 deadline for his third payment, he was in jail.

The Stanton settlement seemed to confirm the worst fears going around the Starr & Co. office. Two senior managers left, taking top clients with them, including Barbara Walters and Martin Scorsese. In the days leading up to Starr’s arrest, two more managers would leave, taking, among other clients, Jeff and Karen Zucker. One Hollywood client who stayed on, oblivious to the trouble, feels shaken by that. “Those people were friends. Why didn’t they tell us?”

In March, Starr told investigators his firm had 200 clients. That would have been true a few years ago; now the number was between 30 and 40, the rest driven away by sloppy bookkeeping or suspicion of wrongdoing on the part of Starr and some of his managers, according to Bloomberg News.

Starr must have known federal investigators were pursuing the Stanton criminal case. He knew the I.R.S. was sniffing around, because an I.R.S. agent had interviewed him about Andrew Stein. The S.E.C. had just concluded its sweep through Starr & Co.’s books in ominous silence. How then could Starr even contemplate taking $7.5 million from his clients’ accounts to buy the triplex condominium, as is spelled out in the indictment? The ex—Starr & Co. insider has an answer that suggests both hubris and self-delusion: “He thought he’d put it back quickly enough that no one would take notice.” To Diane he seemed, in the days before his arrest, newly invigorated. He was on the phone a lot, she recalls, with Gustavo Reyes-Zumeta. Something about a check that Reyes-Zumeta was supposed to send.

Starr & Co. is shut now, its hallways filled with stacks of boxes bearing boldfaced names—Mizrahi, Wachner, Bergen. A court-appointed receiver has warned clients their records will stay in government hands for up to two years. Any money in their accounts is frozen—though the receiver will hear requests for cost-of-living chunks—while government lawyers ponder the dreaded prospect of clawbacks. If Starr took $1 million from Uma Thurman’s account and replaced it with $1 million from Jim and Elizabeth Wiatt’s account, after taking millions more from others, whose $1 million is it? Some clients may even owe Starr & Co. money. Already, the receiver has declared that Martin Scorsese owes $600,000.

As of mid-July, Starr remains in his cell at Manhattan’s Metropolitan Correction Center. To Diane, on her visits, he says he’s working on getting a top lawyer and making bail. But she’s begun to wonder if he has any money at all. His angry clients trade rumors of secret bank accounts; for the three months before his arrest, though, says a knowledgeable source, Starr failed to pay his utility bills and the rent on his old apartment on East 79th Street. Nevertheless, his lawyer, Flora Edwards, hopes to have a bail package prepared by the time this story appears. “Kenneth is looking forward to responding to the issues of the case in court,” she says. “However, it would not be appropriate to discuss the case at this time.”

Starr’s fall has left both his ex-wife and wife in apparently dire straits. Marisa says she has no money. “I have a 15,000-square-foot house with no one helping. I am handicapped. I need a scooter to get around. They are coming to foreclose at any minute.”

Diane, it appears, stands to lose all she gained in her four-year, fairy-tale romance: the clothes and jewelry, the triplex, her dreams of seeing pole dancing become an Olympic sport. One night not long ago, she found herself walking past Harry Cipriani. Inside the brightly lit restaurant she saw fashionable diners laughing at the front table at which she’d sat six weeks before. None looked out through the sparkling glass to see her standing there, simply dressed, alone, the girl in a New York story that had come to an end.