One By One

holden steinberg

“I thought both Angelo and Michael were friends that I would grow old with. As it turned out, I didn’t even have a chance to say good-bye.” One by one, people are dying—quietly—of AIDS. The deaths are most visible in fashion and the arts. Michael Shnayerson reports on the awful decimation of talent.

A few minutes before six, guests begin gathering near the bamboo and the rock pond in the lobby of Japan House in midtown New York. Francesco Scavullo, Polly Mellen, Fran Lebowitz, Cheryl Tiegs, Isabella Rossellini, Iman, Mario Buatta, Cornelia Guest—all have come to pay their respects to a friend, makeup artist Way Bandy.

Programs are distributed. Inside are pictures of Bandy, a man as beautiful as the famous models and socialites whose faces he embellished. Dark hair in a long, English pageboy cut, dark eyes, high cheek-bones. Pasted in at the back of the program is an envelope for mailing contributions to an AIDS-research hospital.

The guests file downstairs, into a large, brightly lit auditorium, and for a while conversations hum. Well-coiffed heads swivel to scan the room; jeweled hands wave hello. Several of the better-known guests arrive fashionably late.

At last Maury Hopson, Bandy’s longtime friend, takes the podium. Looking like Halston, but friendlier, he tells a funny story about the time he and Bandy were awakened in Key West before dawn by a drunken fisherman, stinking of shrimp, who stumbled into the house and passed out. The two chased him away, called the police, and bickered furiously over whether the shrimper’s hair had been rust or gold, his shirt taupe or ocher. “Excuse me,” the policeman finally interjected. “Can you tell me how to spell ocher?”

When the other guests speak, frequent reference is made to the graceful manner in which Way Bandy died, as graceful as the way he lived his forty-five years. “If you ever have the chance,” says Carol Phillips, president of Clinique, “get Maury to tell you the whole story of how Way died.”

After the tributes, guests sip champagne and trade reminiscences. One of the more pensive among them is the actress Sigourney Weaver. She describes how she was away in Europe for a year and a half, and returned to learn that two friends had died untended and alone. “There is still too much turning away from the subject,” she says, “as if it affects only special clusters of the population. But AIDS is here to test all of us—our love, our character, our commitment.”

Something is odd about this evening, but it doesn’t occur to me until later on.

What’s odd is how familiar it has become.

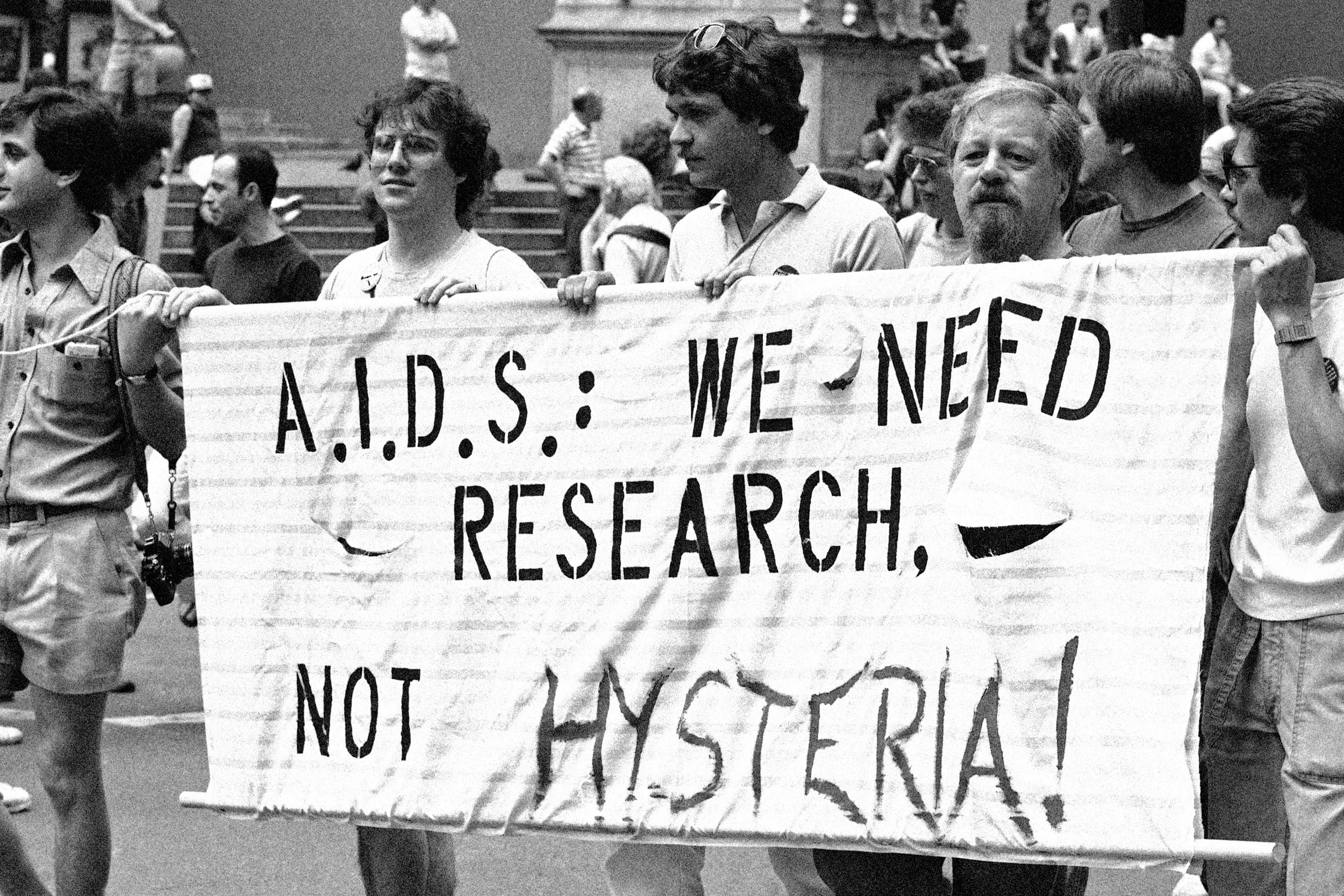

In 1984, an angry writer named Larry Kramer wrote a play called The Normal Heart,which opened at New York’s Public Theater. The play sketched the early effects of AIDS on the gay community, boldly ringing out a death toll of more than a hundred names.

That seems a long, long time ago. Since 1981 some 16,000 people have died in this country because of AIDS, and well over a million may be infected with the virus that causes the disease. The official projections for the next five years have become familiar—a tenfold increase in cases, more than 179,000 deaths in the U.S. by 1991.

Until now the deaths have been clustered in the cities: New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles. Nancy Spiller of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner was told by the obituary writer for The Hollywood Reporter that 30 percent of his listings are AlDS-related. In New York, AIDS is the number-one killer of men between the ages of twenty-five and forty. All of the professions, from Wall Street to the Washington Redskins, have been hit, but in the arts—and its stepchildren, fashion and interior design—the impact has been most visible. Lives are public; so are deaths. And to speak with leaders of those worlds is to hear of dozens of losses.

People are dying, and as they die their absence assumes a peculiar resonance, as if so many children playing in a forest vanished one by one, until the few who remained suddenly stopped to listen to the stillness, and to wonder where their friends had gone.

‘There’s no question,” Joseph Papp says slowly, “that I’m I around people who are terrified. ”

Papp, director of the Public Theater, producer of dozens of plays, and employer to several hundred people, takes a large Montenegro cigar from the box on his desk. “I saw someone this morning who has learned he has AIDS. I’m amazed at the courage of people. He wasn’t destroyed. He talked about it in a very positive way, he’s going to treatments. I told him his job was secure, no matter what. . .But it is sort of a time bomb people are walking around with. I’ve seen friend after friend with it, certainly more than a dozen.”

The cigar remains unlit as Papp muses on in his tough, street-kid voice. “We were doing a play on Vietnam at the same time we were doing The Normal Heart, Larry Kramer’s AIDS play. The Vietnam play was called Tracers. When it came to having both plays performed, at the end of each play, you’d have ten or twelve or fourteen guys not get out of their chairs. Both plays. What would happen is some other guy would come over and put his arm around that guy and stay with this person. The same thing was happening with the Vietnam play—there were veterans down there, couldn’t get out of their chairs. I think when someone is irretrievably lost and dying, you want to give them a feeling of—I don’t want to say hope, but while they are still perceiving and feeling, that they have a sense of people caring.”

Papp’s voice quickens as he becomes the director sketching a scene.

“I found it difficult to watch The Normal Heart when it came to that place toward the end of the play with the two guys, one is withering away and the other is trying to insist that he eat something. And the first guy says, I’m not going to eat anything, I don’t want anything, and the other guy says, You’ll get a lot sicker if you don’t eat anything. I’m sick of you, I’m tired of you, forget it—and he smashes a container of milk on the floor, and it spreads all over, and he throws the bread on the floor. It’s a violent scene, and then it’s quiet, and he turns away, and then the guy who’s stricken with AIDS sort of crawls toward him—”

Suddenly, across the desk from me, Joe Papp puts his head in his hands and begins to cry.

Losses in the performing arts affect a tightly knit community of performers, directors, stagehands—people who work together daily. Matthew Epstein, a vice president of Columbia Artists Management, ticks off the opera-world casualties like baseball statistics: “At the Met, several members of the chorus and musical staff. At the Washington Opera, the managing director. At the Lyric Opera of Chicago, the sales manager. . . ” At the New York City Opera, the first deaths stirred fear as well as sorrow: performers who shared wigs and stage makeup worried that AIDS might be transmitted by sweat. By the time stage director David Hicks died last year, those fears had been replaced by a numbing sense of grief. Hicks, a perfectionist offstage as well as on, wrote his own obituary for the New York Times.

Dancers, until recently, seemed magically exempt: a tribute, said some, to their asceticism. But that may be a misperception. “One of the reasons AIDS seems to have had a lower profile in dance is that in this era of federal budget cuts in the arts, dance companies want to project a more conservative image,” says Richard Philp, managing editor of Dance-magazine. “You know—put on a serious face, show them you’re responsible, and maybe your company will get back some of its money. So it becomes easier not to acknowledge certain kinds of behavior widely associated in the public’s mind with AIDS.” Now such denial is becoming more difficult. In one week last December, a dancer’s death was reported virtually every day, each with the same sad indications: death at an early age, after a long, un-named illness, with parents and siblings listed as survivors. Galvanized by the growing death toll, the triumvirate of Jerome Robbins, Peter Martins, and Mikhail Baryshnikov have agreed to participate in a three-week benefit spectacular next fall.

Judy Peabody, chairman of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, has pitched in on her own. “When I got involved with the Gay Men’s Health Crisis a year and a half ago, serving as a ‘buddy’ to people with AIDS, my friends were a bit taken aback. Even now sometimes I hear intelligent people making off-the-wall statements about transmission,” Peabody says, people who persist in unreasonable fears that AIDS can be communicated by sweat or tears or saliva. “And I’m not as patient as I once was about that.”

A co-leader of a care-partners group, Peabody goes to meetings every Friday, makes frequent hospital visits, and speaks on the phone almost daily with at least a dozen AIDS patients. “They’re really wonderful new friends that I have,” she says, “and they just happen to have this disease.”

AIDS has engendered a more secret suffering in the fine arts. “I think a lot of very important people in the arts are very sick,” says Aladar Marberger, the thirty-nine-year-old co-owner of the Fischbach Gallery on Fifty-seventh Street. “But they aren’t owning up to it. I feel as if there’s a grand dinner party and everyone was invited, but I’m the only one who showed up.” Aladar Marberger has AIDS.

The night before he found out, in October of 1985, Marberger went to a planning meeting for the first Sotheby’s auction for AIDS. His doctor called him at the gallery the next day: results from a checkup had revealed AIDS. “But I can’t have that,” Marberger shouted. “I’m a trustee of the AIDS auction foundation.”

Marberger called friends and colleagues to tell them the news. He was on the phone for sixteen hours. Soon after, he turned over management of the gallery to an assistant. He rented an oceanfront home in the Hamptons last summer for $30,000 and threw party after party. He appeared in local newspapers denouncing the secrecy and fear that shroud AIDS still. Elaine de Kooning painted a series of portraits of him; a band of independent filmmakers did a documentary about him. Only his dentist reacted adversely. When Marberger explained his condition, with a bib on in the chair, the dentist drew back, pleading that for the sake of his children he couldn’t clean Marberger’s teeth. Enraged, Marberger threw a chair through the reception window on his way out.

Now he looks almost healthy, his reddish-brown hair and beard neatly trimmed, his smile quick and radiant, his strong features unmarred but for the faint red spots, the size of quarters, that betray his Kaposi’s sarcoma.

“I have late-night phone calls from all over the country, all over the world. People call me after everyone else has gone to sleep. They have AIDS. They say, ‘How can you do it? How can you deal not only with yourself but with the public?’ I plead with them to be open about it—I did it last night with a major, major figure. He said I must hold his secret to his grave and mine. So I will. But I hate it.”

As entrenched as Aladar Marberger is in the uptown. art world, Martin Burgoyne was in the downtown scene. Burgoyne designed album covers, including one for Madonna. He once found her an apartment next door to his own in an East Fourth Street tenement, and they became close friends. That was years ago, when he was seventeen, when he first came to New York. Burgoyne was twenty-four when I visited him. He too had AIDS.

“When I got sick, they thought I had measles, so I stayed in for a month.” He told me this from the sofa of his Greenwich Village apartment, which was greenhouse-hot. The sofa was covered in a cheerful orange Kenny Scharf print with cartoonish figures in black. On the wall was a portrait of Burgoyne done in pencil by Andy Warhol. On a nearby table were two mischievously painted portable televisions. On another sofa, against the closed windows, sat Burgoyne’s mother from Florida and two female friends, silently listening.

“Now I’m at a crisis point,” said Burgoyne matter-of-factly. “I’m in constant pain. I figure I’ll either get better—or I won’t.”

Lying there, his hair disheveled, a thin earring in one ear, Burgoyne had the wide-eyed waiflike charm of Holly Golightly—but Holly Golightly grown very, very sick. Soon after he was diagnosed, a benefit party was staged for him at the Pyramid Club. Musicians performed free all evening; $5,000 was raised. Burgoyne had one of his friends show me the poster-size benefit invitation by Keith Haring, signed and framed. He had her show me his portfolio, with its album covers, and photo-booth snaps of Madonna taken one day on Forty-second Street and later painted over to striking effect. “I had a dream last night that I went to the art-supply store and there were so many things I wanted,” Burgoyne said. “But I couldn’t have any of them.” In a mordant tone he added, “All I want to do is work, work, work. And I can’t, can’t, can’t.

“But, you know,” he said as I stood up to leave, “as terrible as this is, I’m incredibly lucky. Lucky to have such a bunch of loyal friends now.”

Two weeks later Burgoyne was dead.

There is danger in using war as a metaphor for disease, as Susan Sontag has observed. Yet AIDS has inflicted not only the losses but the same sudden familiarity with death among the young that wartime does. It has instilled a dull, unshakable fear—yanked sharply by every common cold or hint of swollen glands—and wrung a grim maturity. It has also provoked the sort of compassion and courage usually reserved for war. More and more volunteers have signed up to comfort the sick. More and more of the afflicted have the courage not to face death quietly but to seize what remains of life. Max Navarre, a writer with AIDS who helps steer the People with AIDS Coalition, echoes the philosophy of his group when he says with fierce pride that he has no patience with journalists who dwell on the dying. “I was diagnosed in July of 1985. I’ve fought off two bouts of Pneumocystis since then, and right now I’m fine. I know that I’m an unusual case, but I take extraordinary care of myself. And I keep on writing. Look-life in this country will never be the same again. And who else is here to record that but artists?”

For many writers close to the plague, there is a need to put AIDS in some historical perspective. Sontag wrote Illness as Metaphor several years before the first AIDS cases. In her sunlit downtown duplex, she pushes back her thick black hair and answers the obvious question: What postscript to that incisive study would she fashion now?

“It would be difficult,” she admits. “Because it isn’t as if when you scrape away the metaphor you find an ordinary disease, AIDS is, so far, what people thought wrongly cancer was—100 percent fatal as well as mysterious. It makes the metaphors harder to dislodge.”

One commonly heard metaphor about AIDS is that it’s somehow like the Holocaust. Whitney Museum curator Patterson Sims says it’s a holocaust moving bit by bit, person by person. Sontag bristles at that. “The Holocaust was inflicted by human beings on human beings. It’s wrong to compare a situation in which there was real culpability to one in which there is none. And that’s where the analogy leads. The word, like the word genocide, should not be used metaphorically.”

To judge by the latest statistics, what may be happening-at least in Africa—is more like the bubonic plague of 1348–49, which wiped out one-third to one-half of the population of Europe, a devastation felt for two centuries afterward. Sontag points out, however, that AIDS is not a plague in that sense. “It is an infectious but not a contagious disease. Its progress is slow; there is no reason to think that it is simply going to dissipate itself, as did the influenza pandemic of 1918–19 that claimed 20 million lives; and all responsible medical voices agree there will be no quick technological fix, which is, of course, what the public expects of modern medicine.”

Here is one Hollywood AIDS story: a young producer, gay, very much in the closet, issues an announcement that he is leaving the studio to start his own production company. Friends show concern at his obvious weight loss and pallid skin, but to all he steadfastly denies he has AIDS, and goes into virtual seclusion. A year later, his obituary, with no mention of AIDS, appears in Variety. “He did have a few very close friends with him at the end,” one acquaintance relates. “But it was kept very quiet. People who get sick here tend to drop out and disappear.”

The film industry—like the fashion industry, interior design, and architecture—is a commercial art, and from the start commerce has had a predictable effect on the ways in which people react to AIDS. Directly after Rock Hudson’s death came the fears that gay writers and actors and directors would be denied jobs; who knew if they would live long enough to finish a feature film or television series? And would the unions force directors to give blood tests, and ban actors who tested positive?

The unions have won the right for actresses—and actors—to refuse to perform kissing scenes if they choose. But, for the most part, fear in fear-ridden Hollywood has given way to genuine concern. “I think there’s a much more realistic approach than people give this city credit for,” says Barry Krost, a film and television producer who chaired last fall’s second annual AIDS Project L. A. benefit gala with Elizabeth Taylor, which raised $1 million. “There’s been a colossal sense of loss—leading agents, producers, wardrobe people, executives. I know of no one who if I sit down with them to talk about the AIDS Project doesn’t begin the conversation with talk of someone they’ve lost.”

The fashion industry is often charged with having kept its blinders on as one Seventh Avenue company after another lost employees to AIDS. Consumers, it was feared, would shun the racks of designers whose names were associated with the disease. And to stand up against AIDS would, in many minds, confirm the business’s stereotypical image. Last year’s belated industry gala at the Jacob Javits Convention Center came about only because department-store executives put in arm-twisting calls to their wholesalers: if the wholesalers wanted to sell $100,000 of merchandise to the store, perhaps they would be interested in buying a $10,000 benefit table. That—and, say observers, a call from record producer David Geffen to Calvin Klein, persuading him to underwrite the evening for $250,000 so that the take, $480,000, could all go to the American Foundation for AIDS Research (AmFAR).

How much has changed since then? To judge by the apparent unwillingness of designer Perry Ellis to have his cause of death declared as AIDS-related, not much. Shoe designer Kenneth Cole has renewed his public-service advertising, but his is a solitary gesture. Robert Raymond, executive director of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, echoes the party line: “I don’t believe it’s true that fashion has reacted more slowly than other arts. Has the bar association had a benefit? Have the farmers? People always zero in on us, and it’s not fair.”

For rather particular reasons, the interior-design industry moved more quickly than fashion to cope with AIDS. One reason is that it is made up of generally smaller businesses than fashion. The human losses were more quickly noticed. Another is that these businesses sell to the trade; fashion designers sell to the public, and their brand names are more easily tarnished. Decorators—and, as often, the manufacturers and actual designers behind them—could more easily afford to speak out. Almost three years ago DIFFA—Design and Interior Furnishing Foundation for AIDS—started as a New York-based nucleus of three people. Today, it has over five hundred volunteers, four committees in other American cities, and has raised $700,000. Its chairman is Interiors magazine publisher Dennis Cahill, a husband and father. “When I first got involved with DlFFA,” he says, “word filtered back to me from acquaintances who said, ‘My God, I guess he’s bisexual.’ That was all right. This was the first unpopular cause I’d been involved with for quite a while; it was sort of fun.”

Still, AIDS retains its stigma. For nearly two years, designer Angelo Donghia kept the truth of his condition from such close friends as film producer Joel Schumacher and Architectural Digest’sPaige Rense. Told toward the end, the friends were sworn to secrecy. “I’ve gone through this so many times that I tend to forget what the cover story is for each one,” says Rense sadly. “Another friend of mine, the designer Michael Taylor, didn’t want anyone to see him when he was sick. By the time it was acknowledged, he was no longer lucid.

“I thought both Angelo and Michael were friends that I would grow old with,” Rense adds. “As it turned out, I didn’t even have a chance to say goodbye.”

Against the backdrop of all this illness and death, the true leading characters work on: in hospitals and research clinics, daily revising their estimates of how severe and pervasive AIDS is and will be, struggling toward what could soon be a vaccine, or just a better treatment—or not be one at all.

“There is no precedent for AIDS,” declares Dr. Mathilde Krim, a research scientist at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, co-founder of the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and wife of Orion Pictures’ Arthur Krim.

Dr. Krim, who has received me in the library of her East Side town house, ticks off the big diseases of the last two hundred years. “Syphilis? It’s probably true that certain groups were harder hit, but still it was indiscriminate. The flu of 1918? That was highly infectious as well as contagious, transmissible by casual contact, and again selected no particular group.”

AIDS does select certain groups. But then the lines begin to blur. “It’s interesting to follow the routes AIDS is taking in Europe. One route is from the Africans. Another is the gay community, and there you see it spreading out from the airports of major cities—such as Stuttgart and Frankfurt, Geneva and Paris. Clearly these are cases carried by gay men. The third route is in Germany, which bought American-made factor VIII—the blood-clotting product for hemophiliacs that turned out to be contaminated. . . But this is the very beginning of the disease’s course. Soon many more women, for example, will get it.” (In fact, the incidence of AIDS among women is growing. Two recent cases: independent record producer Lyn Hilton, who contracted the virus from her lover; and the wife of well-known record producer John Hammond, Esmé Hammond, who received contaminated blood.)

Dr. Krim is a rather small woman who wears her hair in a bun and has a matter-of-fact air that belies the passion of a crusader. “I’m interested in research; the fundamental answer, after all, is vaccines and treatment. But I’m also interested in trying to reach the public. Education is especially important because there’s no one government report yet. And that’s why the surgeon general’s report and the National Academy of Sciences report are so important.”

The Academy of Sciences report is the one that projected 270,000 AIDS cases in America by 1991 and 179,000 deaths. Dr. Krim believes far more people will have actually contracted AIDS by then, but she also believes that fewer will have died. “I think AIDS will be preventable; we’ll be able, that is, to suppress the virus, but it will be there all the same. Safe sex will still be necessary. And we’ll have many men and women who can’t think of marriage with children as a life goal.”

If this picture seems harsh, Dr. William Grace, chief of oncology at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York, draws one that is all but apocalyptic.

“Every ten to twelve months the number of AIDS patients doubles—everywhere,” Dr. Grace says. “Right now at St. Vincent’s 45 medical beds—of our 316 beds available—are occupied by AIDS patients, and most of these are middle-class patients, not the drug users or others without medical coverage, who get sent to Bellevue. What happens next year, when we have ninety patients? And 180 the year after that? In four years we will have exhausted all the medical beds in New York.”

Dr. Grace is absolutely blunt about it: “I think AIDS is going to devastate the American medical system,” he says. “Last year, coronary-bypass surgery cost $1 billion in this country—and that was very expensive. In 1985, the 12,000 patients with AIDS cost this country $6 billion. Do you realize that in five years there are going to be over a quarter of a million cases? The virus is already incubating in one million people, and what we’re seeing now is that the incubation period can be eight or nine years. We’re also seeing that a steadily growing number of those with the virus are actually getting AIDS. We’re also seeing other viruses like the AIDS virus—viruses that haven’t even been discussed in the press. There will be many, many more.

“The sexual revolution is sure over,” says Dr. Grace as we walk out together into the brisk evening air. “I’ll tell you, my daughter is eight years old, and I’m educating her right now.”

A few days later, I visit Maury Hopson. I want to hear the story of how Way Bandy died.

“I’m not sure when Way really knew, because he was incredibly private,” Maury tells me. He is a gracious man with a soft southern drawl. “We did both have the possibility of death on our minds, of dying young, as so many people we know have and are. But there was a kind of acceptance already about death, so that we really didn’t discuss the death part; we really discussed the kind of cleansing of the temple.

“As he began to get sicker, it was hard to talk about it, because he could find ways to call it something else. Also, it was really literally the last two weeks of his life that we were alarmed. We had not talked about AIDS; we talked about bronchitis, we talked about the possibility that he had pneumonia, we talked about his weight loss. But then, he always did want to be rail-thin.

“When he actually got to the hospital—after collapsing in Francesco Scavullo’s studio—the doctor said he had the pneumonia, but that if the antibiotic took effect Way could be out in three weeks.

“He was in this awful little room just off the elevator. And anyone could look in—I really half thought a New York Post photographer would find out and come take pictures. But it turned out that the head nurse remembered me—I had done her hair at her wedding nineteen years ago. And we had some other pull. So we were able to move him to the Stavros Niarchos suite, overlooking the Fifty-ninth Street bridge and all of Manhattan.

“And then things changed; it became a more graceful time. He would come out of a dream and say, What’s going to happen now? I’d say, Well, you’re still sick, and until this antibiotic takes effect you’re just going to have to stay here. Then he’d go back to sleep and come out of it and say, Well, they told me the pneumonia’s gone. But it’s not gone, I would say. He’d say, They came in and told me it was gone. I’d say, No, you were dreaming.

“We had all his toiletries and perfumes, and he had me douse him in them. I kept his hair combed and his lips moistened with special cream, and I’d sit him up and start putting his cologne on him. I’d say, How much? and he’d say, Pour it on, because he wasn’t able to take a shower or bath, and he was furious about that—they didn’t have an apparatus for the oxygen in there.

“Wednesday night, we knew he was going. I sat and held his hand a long time, and he would squeeze my hand with his eyes closed, but his breathing was coming harder, and I just told him to let go, you know. I said, You’ve already done everything so right, and there is really no reason for you to come out of this, because it only gets worse when you come out of it. Until there’s a cure, you come back and the next process starts, some other awful part of the disease. And I said, Let go, everything about you is prepared. He raised his eyebrows and squeezed my hand, and he kind of went ‘Hmmphh,’ and that was it.

“I looked at him then, and I said, I’m so proud of you—look what you’ve done, you’ve just slipped over to the other side. And I was crying, of course, but I was also kind of delirious with happiness that it had been so painless, and that he had done it with such bravery. I mean, here was this person who was like a makeup artist that you think is some big sissy. And he had gone out like a fucking gladiator.”